Introduction

In the history of education in Harlem, students are portrayed in a number of different ways. They have been described as helpless, damaged, underserved, or deserving better. Regardless of the range of words used to talk about and understand the experiences of students in Harlem, it is rare to hear about schooling from the student’s perspective.

This exhibit’s main goal is to share Harlem resident Barbara Wilson-Brooks’s account of her experiences as a student in East Harlem and Upper East Side schools from 1966 to 1979. Her memories and stories provide a rich, joyful portrait of Harlem schools that is not always evident in reports of the time period and scholarly works.

Although the focus is on Wilson-Brooks and her view of her community, it is essential to put her experiences within the broader history of Harlem schools at that time. Wilson-Brooks attended elementary and middle schools in the Intermediate School (IS) 201 Demonstration District, including IS 201 itself. The demonstration district – an experiment in local community control of schools – was authorized by the Board of Education in 1967 and included IS 201 and its area elementary schools. In 1968, the conflict over community control led to a teachers’ strike and the closing of the city’s public schools for six weeks.

Wilson-Brooks was a second grader during the 1968 teachers’ strike. Her experiences of the demonstration district and the 1968 teachers’ strike provide individual insights into these larger histories.

A Harlem Community

There are many different ways to define a community, especially in a place like Harlem, which has a rich and diverse history. While the Board of Education and others drew boundaries to define the IS 201 Demonstration District, people who have lived in that neighborhood may have different thoughts about their community’s meaning and its and its borders. In Wilson-Brooks’s view of her community, for example, teachers, parents, and even the police knew and supported each other. Additionally, since many of Wilson-Brooks’s teachers also lived in the community in which they taught, Wilson-Brooks and her classmates did not only see their teachers in school, but as active participants in their everyday life outside of school. Subsequently, for Wilson-Brooks, community represents a social space in which people feel a connection to one another rather than a mere geographical space.

Perhaps for this reason, the specific term “IS 201 Demonstration District” does not figure prominently in Wilson-Brooks’s recollections. It could be because she was young at the time when the Board of Education authorized the demonstration district. It also seems, however, that community and activism represent much larger ideas and time periods for Wilson-Brooks than just the IS 201 Demonstration District from 1967 to 1971. Wilson-Brooks envisions community and activism as residents’ involvement in the constant improvement of a neighborhood and its services and institutions. Similarly, community control advocates focused on schools, but many also sought to improve other aspects of the East Harlem area as well. Subsequently, although Wilson-Brooks may not speak in terms of the demonstration district or does not remember the fight for community control at that time specifically and prominently, her overall understanding of community aligns with the ideas that motivated community control.

Wilson-Brooks’s memories and recollections of the community as a student are still strong today. As a current resident of the neighborhood, she is surrounded by a number of the people and places of her youth. In January 2014, for example, Wilson-Brooks gathered with many of her classmates from PS 133 for a memorial service for her principal, Mr. Jackson. The feeling of a close-knit community was still present.

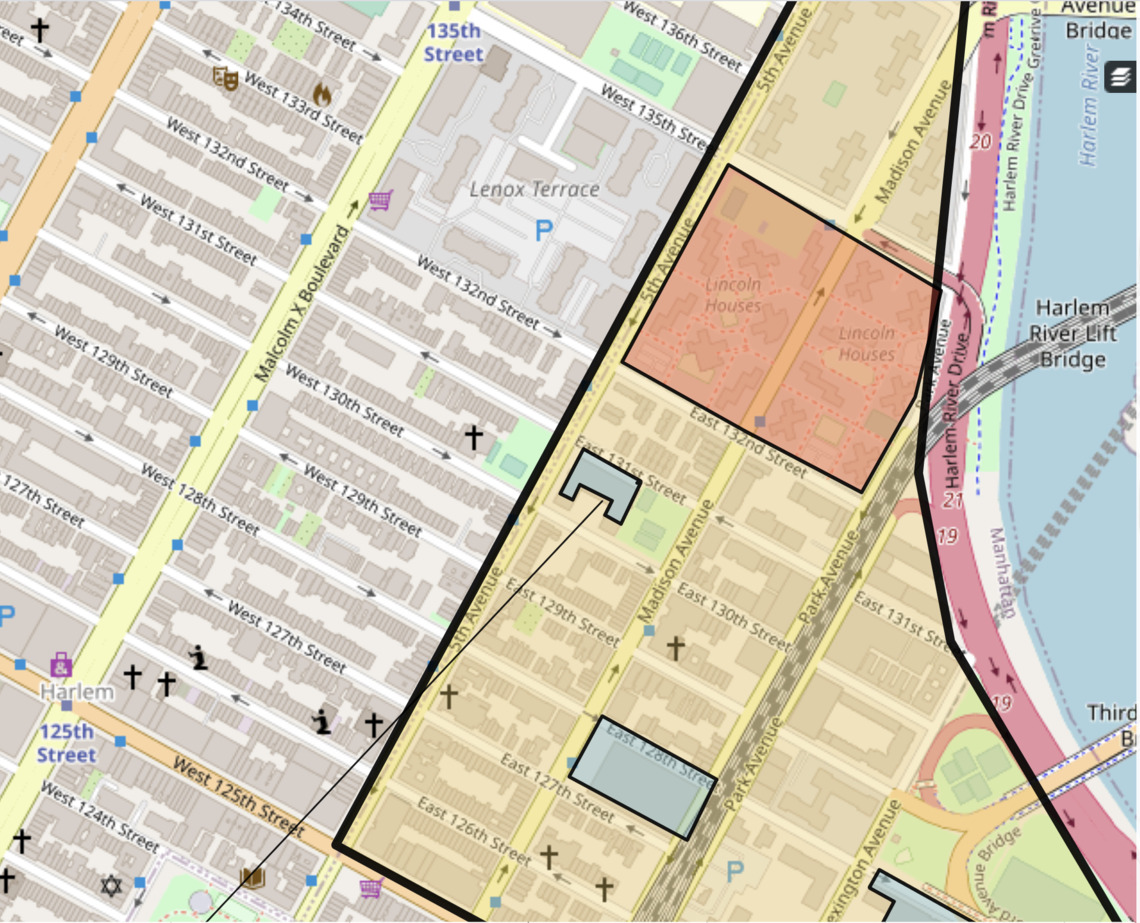

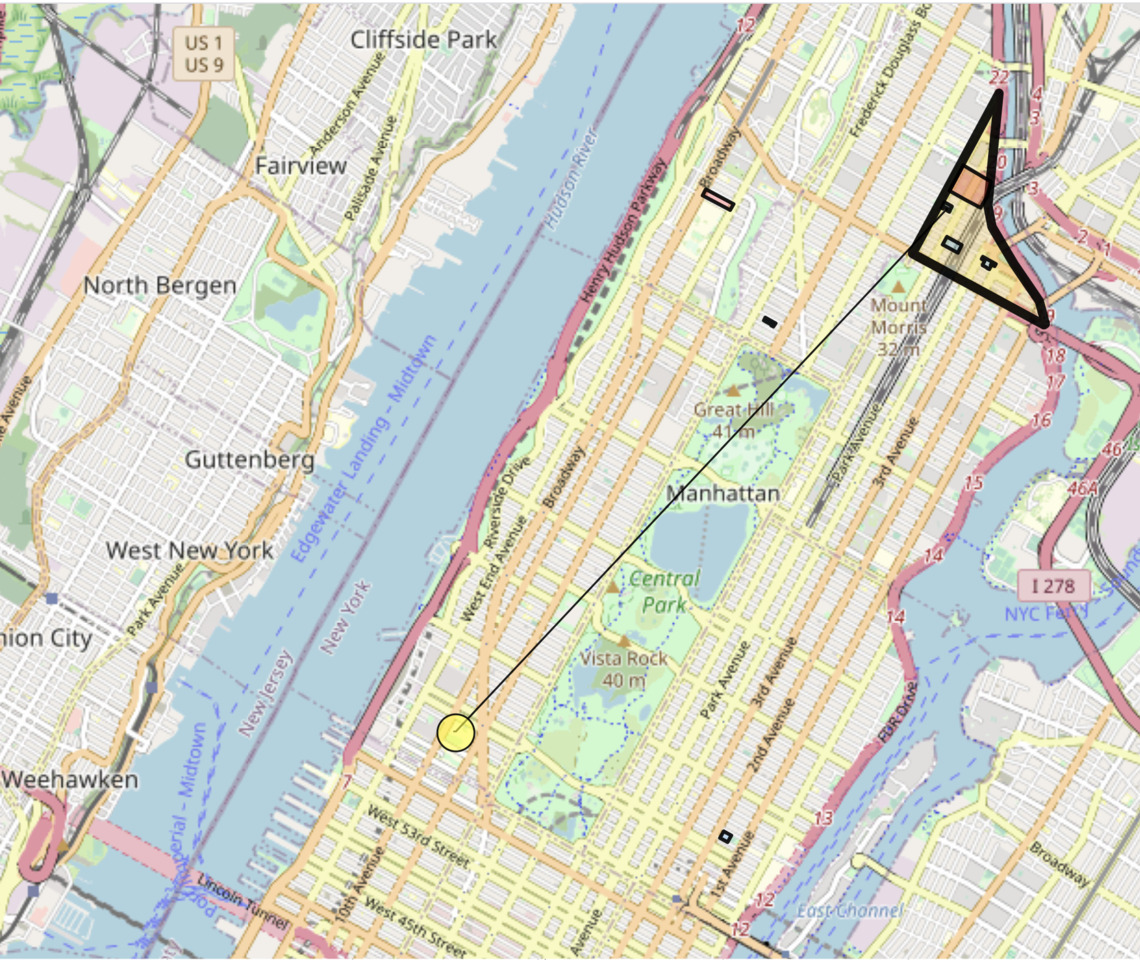

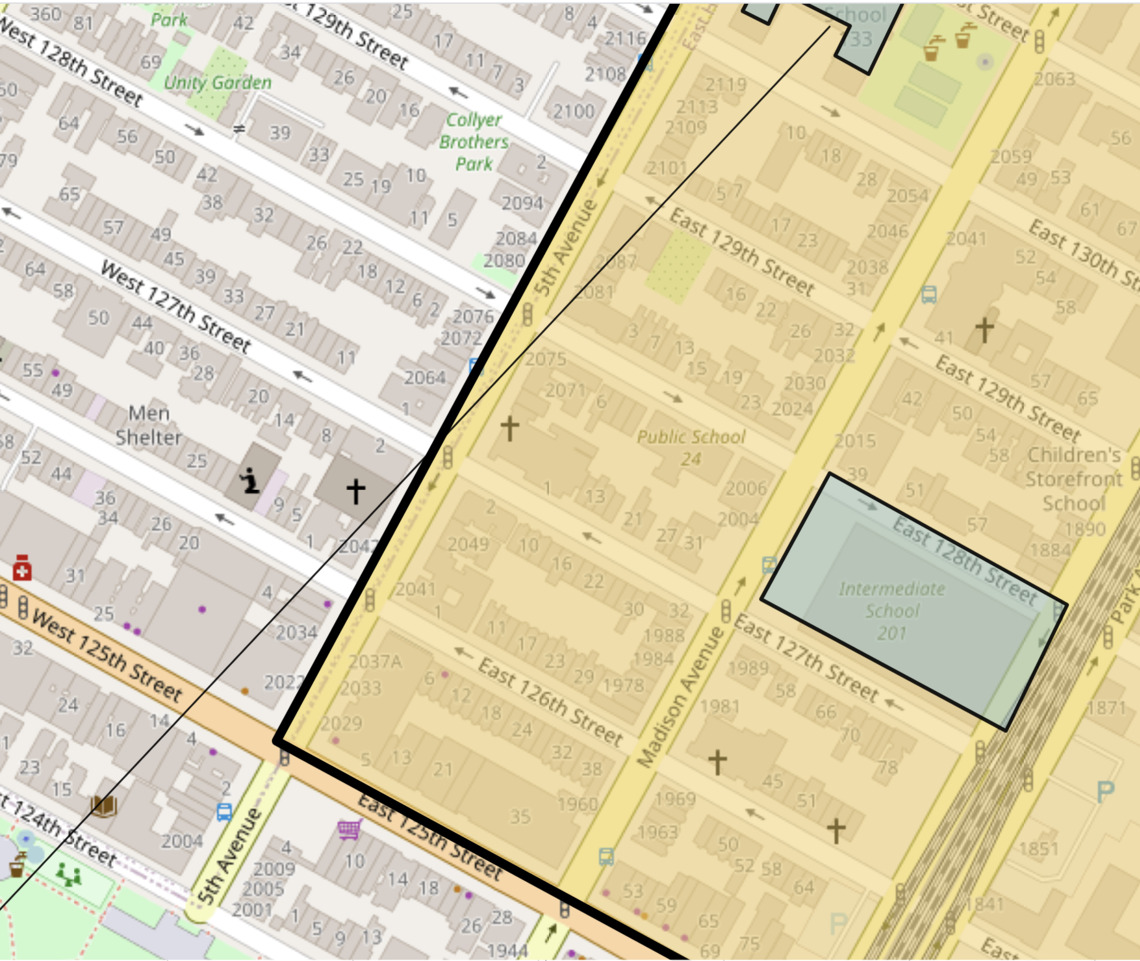

The black triangular outline drawn on the map marks the demonstration district and encompasses all the schools Wilson-Brooks attended (PS 133, PS 31, and IS 201) as well as her home.

Home

In 1965, when she was four years old, Barbara Wilson-Brooks and her family moved from Georgetown, South Carolina to the Abraham Lincoln Houses, a public housing complex in East Harlem, New York.

She had a younger brother and a younger sister. Her father was a truck driver, and her mother was a nurse. Wilson-Brooks’s aunt, who is eleven years older than Wilson-Brooks, also lived with the family until Wilson-Brooks was about fifteen. Her aunt cared for the family, and also was Wilson-Brooks’s good friend and confidante.

Nearly all of Wilson-Brooks’s neighbors were African-American families. Many worked for New York City government departments, such as the MTA, the Department of Sanitation, or the NYPD.

Wilson-Brooks remembers the Lincoln Houses as a close-knit, family-oriented environment. She knew many of the families in the buildings and spent lots of time with the other children in the complex. To hear more about the morning routine of going to school in the Lincoln Houses, play the clip below.

IS 201 Demonstration District

In 1967, the Board of Education authorized the IS 201 Demonstration District - an experimental project in which the community oversaw the direction of students’ education.

The IS 201 Demonstration District plays an important role in the history of education in Harlem in the late ’60s and early ’70s. It roughly covered the territory outlined on the map and served students and families living in those areas. Students attended PS 24, PS 39, PS 68, or PS 133 for elementary school. These were feeder schools for IS 201, which students in the district would attend for junior high school.

The district came about because parents and community activists believed that schools in the area did not have the same quality of resources, facilities, and teachers as schools serving children in predominantly white neighborhoods of the city. Earlier efforts to address this inequality via desegregation had failed. Families in other areas faced similar issues and had similar concerns, and in 1967, the Board of Education also authorized demonstration districts in Ocean Hill-Brownsville in Brooklyn and the Lower East Side in Manhattan.

The most famous of the demonstration districts is Ocean Hill-Brownsville in Brooklyn. In 1968, when Wilson-Brooks was in second grade, community boards overseeing schools attempted to fire unionized teachers in order to hire teachers the board selected. In response to the firings, the United Federation of Teachers held a strike. As a result, in 1968, for most New York City students, school did not start in September, but only after Thanksgiving.

However, many teachers in Harlem schools and the demonstration districts chose not to strike, and their students attended school. Wilson-Brooks remembers attending school during the fall of 1968. Although she does not remember exactly what the strike was about, she states that her school was open and parents and school staff made a point of going to work; they wanted to keep the school open as an important community center despite outside issues and tensions. In the following clip, Barbara explains memories of her non-strike in greater detail and also describes ideas of activism in PS 133.

PS 133

Barbara Wilson-Brooks attended PS 133 from kindergarten through fifth grade. Wilson-Brooks states that she received an excellent education at the school. In her view, teachers provided quality instruction, and students strove to do their best. When talking about PS 133, Wilson-Brooks said “that school really stood out for me because […] we learned[…] that’s where we blossomed. Everybody cared about us. […] I can remember from my kindergarten teacher, Ms. Stevens, the care they took, the teachers, to teach us to read, to write. So each time we progressed, it was like each teacher knew one another, knew what was expected, so that when we go to the next grade or the next class, it was already set up.”

Wilson-Brooks has many fond memories of PS 133 and her teachers. Out of her entire schooling experience, her memories from PS 133 are the strongest even though they are her most distant school memories. She remembers all of her teachers and has a story about each one. Wilson-Brooks’s stories present a dynamic, caring, and close-knit school community that are best heard in her own voice. Some accounts that stand out are the way that Wilson-Brooks remembers Ms. Steinberg’s hugs and the smell of her perfume, Ms. Burrell’s strict yet caring demeanor, Ms. George’s love of opera, and the first time that Wilson-Brooks saw Ms. Chandler wear pants. To be immersed in Wilson-Brooks’s memories, listen to the audio clip below. This clip is long, but the stories are entertaining and Wilson-Brooks is an engaging speaker.

Learning Outside of the Classroom

As a student at PS 133, Barbara’s teachers exposed her to many learning and cultural experiences outside of the classroom. Two significant places in Barbara’s memory where learning took place are Lincoln Center’s Opera House and The Studio Museum of Harlem, which at the time was located in the National Black Theater’s current home.

Barbara’s third grade teacher, Ms. George, was an opera singer and shared her love of opera with the students. She taught them arias of a certain opera, and as a class, they went to Lincoln Center to see the opera. They even got to go backstage to visit Leontyne Price, a famous opera singer. Price also visited PS 133 that year, and a New York Times article about her visit shows a picture of her singing “Silent Night” while a young student sat on her lap.

Barbara’s art teacher also provided her and her classmates with enrichment opportunities at The Studio Museum of Harlem. She and her classmates would go to the museum and receive lessons from the Museum’s founders. Barbara’s art teacher stayed in touch with her after she left PS 133 and helped her to develop a portfolio over the years. When it came time to apply to high schools, the teacher encouraged Barbara to look at Arts and Design School, but at that point, Barbara was not as interested in art.

PS 31

Barbara Wilson-Brooks attended PS 31 only from 1972 to 1973, for sixth grade. After Wilson-Brooks graduated from PS 133, her mother did not want her to go to IS 201. After seeing and reading about protests at the school, she was concerned, as her daughter recalled, that “Oh, there’s so much going on with that school. It’s too bad!” To avoid attending for as long as possible, her mother sent her to PS 31 - not a feeder school for IS 201.

Although PS 31 does not figure as prominently in Wilson-Brooks’s memories as PS 133, she remembers PS 31 as a good school with many opportunities to pursue, including art and music. Additionally, Wilson-Brooks remembers PS 31 as a school that taught students to think beyond the school curriculum and to consider what was going on in the world.

IS 201

The construction of IS 201, a windowless, air-conditioned building and one of the city’s first intermediate schools, began in 1964. As a response to community pressures for integration, school officials promised that the new school would be integrated. However, the zone they designed included African Americans and Puerto Ricans without any white students. In 1966, the year IS 201 was supposed to open, parent and community activists demanded that the community should have the power to set educational and administrative policies in their schools. They called for a community committee to select the principal and the teachers of IS 201. In order to achieve these demands, the parent and community activists tried to keep IS 201 closed by boycotting IS 201 as well as other schools in Harlem until their demands were met. Despite protests, IS 201 eventually opened on September 21, 1966. The school opening broke the boycott, but not the larger battle for community control. In 1967, the Board of Education authorized the IS 201 Demonstration District.

Barbara Wilson-Brooks attended IS 201 for seventh and eighth grade, from 1973 through 1975. Originally, Wilson-Brooks was nervous to attend the school because of the stories of protests that had taken place around IS 201 before the creation of the Demonstration District, and a few years later when parents and community members sought the appointment of an African American principal. Once Wilson-Brooks attended, though, she enjoyed her time at the school and believed she received a good education. In her recollection, teachers had high expectations for students and used a variety of instruction methods and resources. She called it “another school that was dynamic.”

She has strong memories of the school’s unique architecture, especially its windowless design, which had been a major point of community criticism of the school. The only floor in the building that had windows was the ground floor. This level housed the administrative offices as well as entrances and exits. Science labs were below the ground level, and all other classrooms were above it. Wilson-Brooks, and others at the time, believed that the school had such a distinct design and high quality facilities (such as air conditioning and a large auditorium) because they thought it originally was planned for white as well as African-American children as part of desegregation efforts. In the following clip, Wilson-Brooks explains more of the controversy surrounding initial plans and designs for IS 201.

By the time Wilson-Brooks became a student at IS 201 in 1973, she could not detect any traces of protests she had earlier associated with the school. The demonstration district no longer existed, having been replaced after the 1968 teachers’ strike by a much weaker form of community governance called decentralization. Instead of an IS 201 demonstration district, a larger area of East Harlem had a local school district with an elected school board.

However, Wilson-Brooks did not only recognize activism as a protest or action in moments of tension. Instead, she astutely characterized teachers’ continuous efforts to teach students about their heritage and about community issues as activism. Wilson-Brooks saw that Black pride was prominent around her at IS 201, with people wearing dashikis and using Swahili terms. Additionally, her teachers taught her about Black Power, African and African-American history and culture, and she was also aware of movements and groups like Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and United Black Association (UBA), but while she was a student she did not link these protests to the school’s connections to community control. Not until later, when she read about the protests at that time did she fully realize this part of her school’s history. Hear more about Wilson-Brooks’s experiences around Black empowerment at IS 201 in the audio clip below.

Julia Richman High School

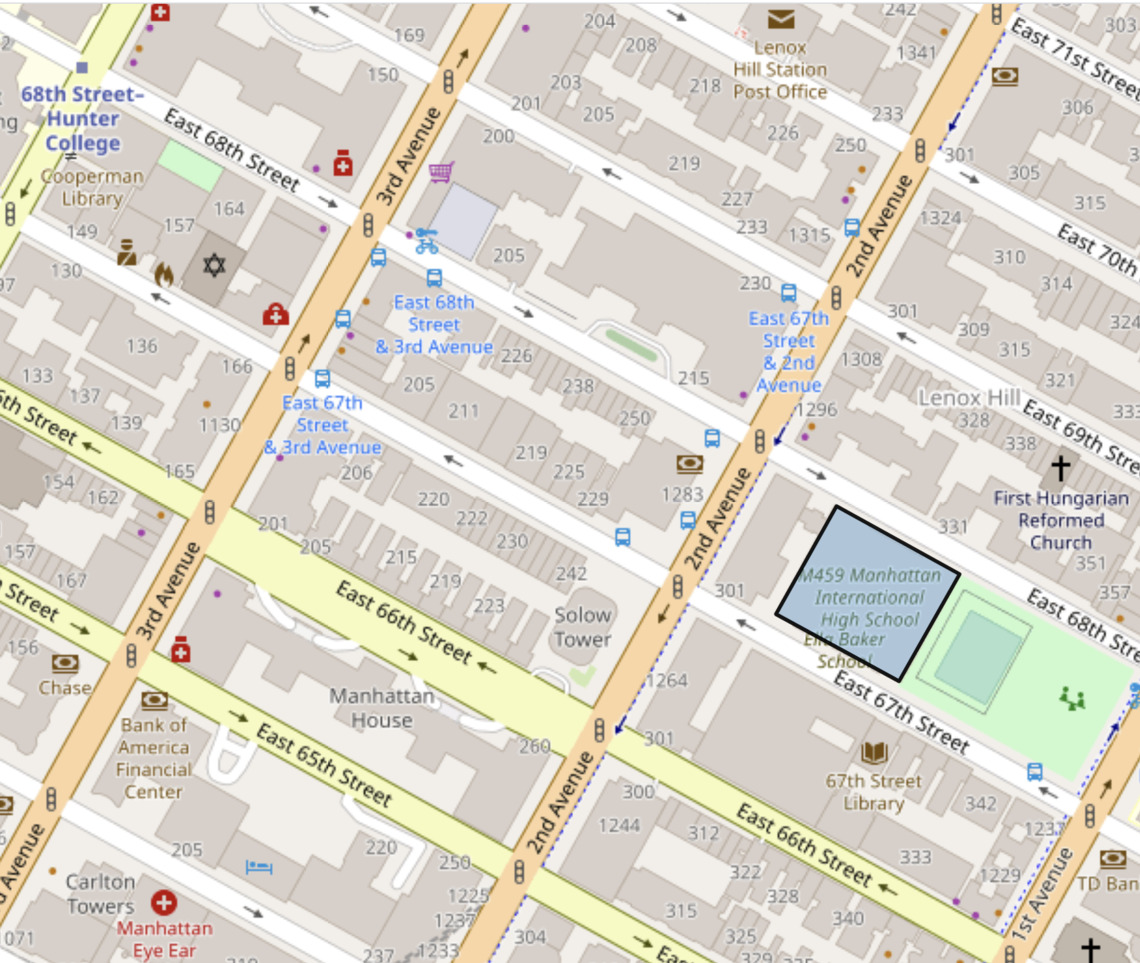

In 1975, as Barbara Wilson-Brooks was planning for high school, there were limited academic high school options in Harlem. For high school, Barbara Wilson-Brooks considered attending Julia Richman High School on the Upper East Side or Brooklyn Technical High School. Ultimately, she chose Julia Richman, which many of her friends from her Harlem community attended as well, so that she would neither have to travel so far as Brooklyn nor all by herself.

Wilson-Brooks was an honors student at Julia Richman and a member of the College Bound program, a program that geared students towards college. Although she saw drug use and violence at the school, Wilson-Brooks focused on her school work and kept on task. She remembers high school as a time when she expanded her world and what she knew, since this was one of the first times that she regularly left her Harlem neighborhood. Additionally, many of her classmates were her neighbors, but there were also a number of Latino, especially Puerto Rican, students from El Barrio, a section of East Harlem centered around 116th Street. Gene Anthony Ray from Fame and Laurence Fishburne also were her classmates. In reference to her famous peers, Wilson-Brooks remarked, “…you know how you never know who you’re passing?”

Family Academy (PS 241)

Barbara Wilson-Brooks remembered that her teachers often told her, “Always come back to your community in some way. Find a way to come back and serve your community.” Although Wilson-Brooks may not have come back to the specific neighborhood she grew up in, she stayed committed to the broader Harlem community and pursued a career in education, serving and supporting her community the way she was served and supported when she was a student. From 2002-2004, for example, Wilson-Brooks worked as the executive assistant to the principal of Family Academy, an elementary school in Harlem, and she currently works in the Office of Teacher Education at Teachers College, Columbia University, supporting teachers-in-training as they receive certification.

Throughout her career, Barbara Wilson-Brooks has held positions at community organizations and city departments, including the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, the New York City Department of Education, and the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

While working at Family Academy, Barbara learned about how public schools worked and also gained a new appreciation for her teachers. During an interview with Barbara, she repeatedly said that she wished she could give the kind of education she received to children today. In some ways, her work at Family Academy and other educational institutions, has allowed her to do so. In the following clip about her experience at Family Academy, one of the first words she uses to describe her work is exciting. Despite the bureaucracy and challenges she dealt with, Barbara still viewed the school environment as exciting.

Wilson-Brooks worked at Family Academy in the years in which several of the decentralization reforms put in place during her elementary schooling came to an end, as Mayor Bloomberg (with state approval) re-centralized the New York City school system. As a student, her community fought to gain control and direction of its students’ education in local schools, eventually forming the IS 201 Demonstration District. In 1971, the demonstration district dissolved, but local school boards kept in place some local “decentralized” control of schools. Decentralization lasted until 2002. Under decentralization, Family Academy developed its own curriculum. The school raised money to supplement its budget from the city. The students largely came from low-income families, and teachers, administrators, counselors, and social workers believed in all students’ abilities and often advocated on their behalf. The school also extended classes and services to families. In Wilson-Brooks’ view, re-centralization under Mayor Bloomberg brought a more standardized curriculum, and Family Academy lost the autonomy it had enjoyed before. To learn more about Family Academy, see this New York Times article.

Today

Barbara Wilson-Brooks still lives in Harlem, just blocks from her childhood home. She and her family love Harlem and plan to stay. Wilson-Brooks is committed to being a member of her community and to helping address the issues facing it, including education and poverty. She notices the changes that have been taken place in Harlem and appreciates what she calls the increasing diversity visible today. While she believes that hospitals and services are improving, she knows there are still many issues that her community must work on together. Today, Wilson-Brooks works at Teachers College, supporting teachers-in-training as they receive certification, and as Wilson-Brooks sees it, providing schools with the best teachers possible. To hear more about Wilson-Brooks’s love of Harlem, listen to the clip below.

Reflection

From Nina Wasserman, who interviewed Barbara Wilson-Brooks and designed this exhibit:

I conducted research in preparation for this exhibit and worked with Barbara Wilson- Brooks during my first semester of student teaching as I studied and trained to become a high school history teacher in New York City. While working on the exhibit, I appreciated that I was able to intimately learn the history of the system and institution of where I teach. I learned how important it is to understand the context and history of the school, neighborhood, and city where I teach. Although Ms. Wilson-Brooks and I spoke about Harlem and I teach in the Bronx, her story helped me to understand the long history of education in this city and students, families, teachers, and administrators’ various roles within it. It was even more significant that I was able to learn about this history from a student, as those are the voices that often are left out of conversations about education, both in historical scholarship and current policy and planning.

Furthermore, this project, including the research, conversations with Ms. Wilson-Brooks, and reflection with other students in the course, taught me that we should not only think of schools as places of learning. They also are important places of community. At times, this can be hard to remember while focusing on lesson planning and other daily tasks of leading a classroom, but at an early point in my career, my work on this exhibit emphasized the idea and importance of community in teaching.

Listen to the complete interview with Barbara Wilson-Brooks.

To learn more about the IS 201 Demonstration District, other demonstration districts, and the 1968 strike, read Diane Ravitch’s The Great School Wars: A History of the New York City Public Schools (Basic Books, 1985) and Heather Lewis’s New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and its Legacy (Teachers College Press, 2013).