In the early 1960s, civil rights organizers in American cities designed a new and unique response to the urban and educational crises unfolding around them: hiring local residents, primarily the mothers of schoolchildren, to work in public schools alongside teachers. Such hiring, they argued, would accomplish three essential goals: improve instruction, build links between schools and communities, and create jobs and careers in education.

Black, Latinx, and Asian-American New Yorkers led this movement for local hiring. Working with allies in antipoverty programs and teacher unions, they created experimental programs and used them to convince the New York City Board of Education to hire over 10,000 working-class women as community-based “paraprofessional” educators between 1967 and 1970. The ideas and programs they developed in New York City became national models. In response to their efforts, Congress wrote funding for local hiring into federal law. American school districts used it to hire half a million community-based educators between 1965 and 1975. Para programs transformed the social and institutional geography of public schooling, creating thousands of jobs and leadership roles for working-class women in deindustrializing cities.

Today, over 28,000 paraprofessional educators work in New York City schools, out of 1.2 million nationally. We know these educators by many names: teacher aides, teacher assistants, auxiliary teachers, and most commonly, paraprofessionals, often shortened to “paras.” They provide individual support to special-needs students, work alongside teachers in overflowing classrooms, lead small groups in bilingual programs, and supervise lunchrooms, hallways, and schoolyards. Paras are far more likely than teachers to live near the schools where they work, and they utilize local knowledge to improve instruction and facilitate communication between students, parents, teachers, and administrators. Despite their ubiquity, however, little is known about the origins of “paraprofessional” jobs at the nexus of the Civil Rights Movement and the War on Poverty half a century ago. The social movement origins of these jobs, and the educational transformations envisioned for and by paras, are seldom recalled in educational scholarship, policy, and activism.

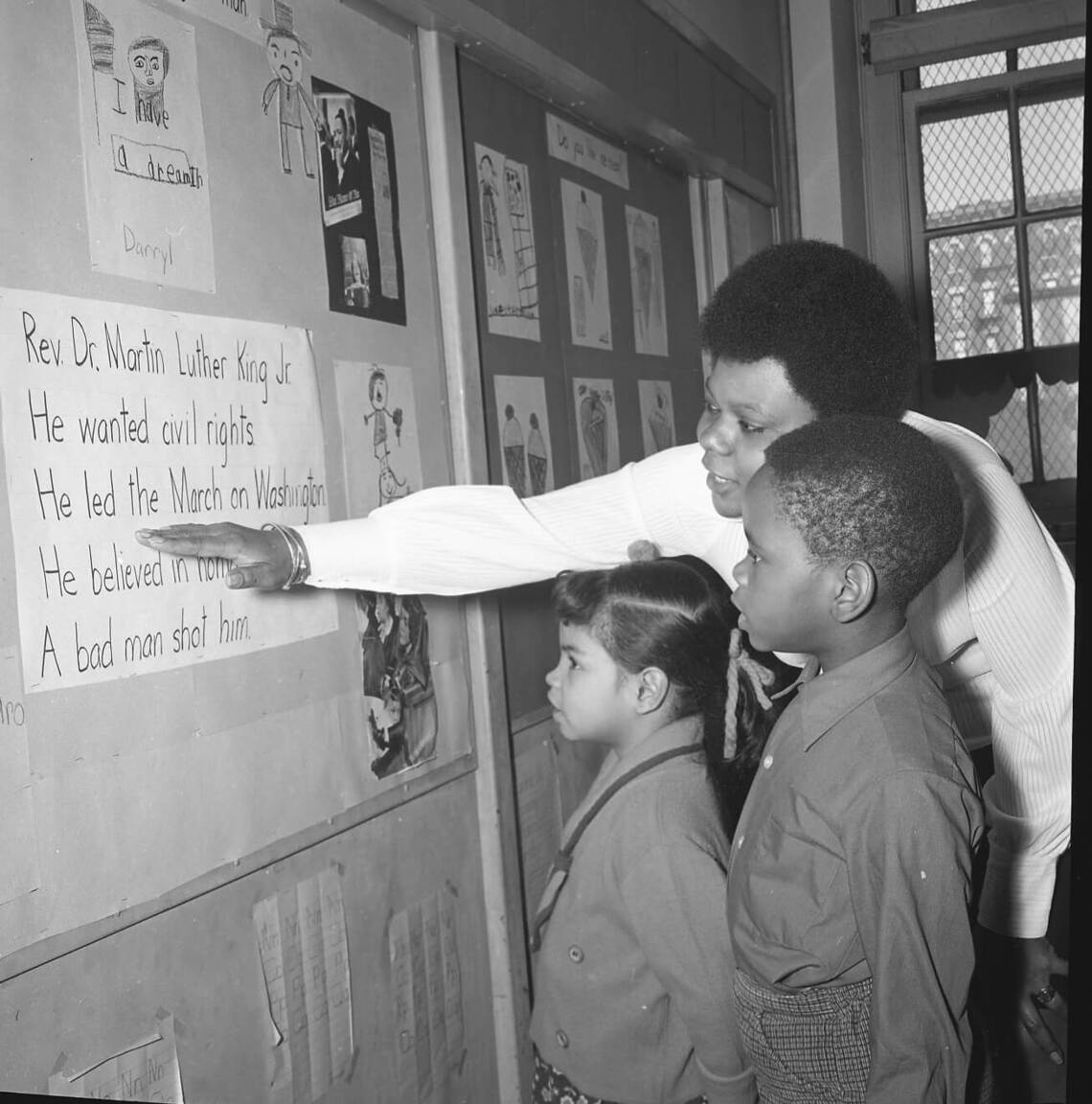

Like the movements from which they emerged in the 1960s, paraprofessional programs were a national phenomenon with innumerable local iterations. This exhibit tells the story of the Parent-Teacher Teams program, which hired parents to work alongside teachers as community-based paraprofessional educators in third-grade classrooms in Harlem and the Upper West Side from 1967 to 1970. A coalition of parents, educators, activists, and scholars came together to create this program amid tremendous conflicts over parent involvement in public education in New York City in the late 1960s. In doing so, they built on models developed in Harlem over the preceding decade. At its height, Parent-Teacher Teams employed 130 local residents in 27 schools, where they served 3,900 students and earned rave reviews from parents, teachers, administrators, and local activists. While there is no “typical” para program, studying Parent-Teacher Teams offers a window into the world of community-based education in the late 1960s, revealing the innovations and possibilities generated by these programs.

Paraprofessionals in NYC Bring Community into the School from American Federation of Teachers on Vimeo.

In the video above, exhibit creator Nick Juravich talks with former paraprofessional Shelvy Young-Abrams about this exhibit and about the impact paraprofessional educators made in classrooms and communities. The work of parents in these roles raises fundamental questions about public education. Who educates the children of the city, and with what legitimacy and credentials? What relationship should educators have with the students, parents, and communities they serve? How are opportunities and resources distributed by schools, and how can people organize to impact these processes? These were urgent questions when Parent-Teacher Teams was created, and they remain urgent today as educators and policymakers consider, among many pressing questions,new ways to connect school and community and new strategies for recruiting Black and Latinx teachers.

What does a focus on the lives and labor of these working-class, Black and Latina woman educators reveal for scholars, educators, and activists today? Para programs rested on two foundational ideas: that public schools required sustained community involvement to succeed, and that these schools could provide collective empowerment and advancement for communities, not just particular skills for individual pupils. The campaign for paraprofessional jobs was a successful part of the struggle for educational self-determination and the equitable distribution of school resources in Harlem. Paras brought the practice of activist mothering into public schooling, improving classroom education and undermining assumptions of pathology in Harlem. These women mobilized the pride and power present in their communities, but they also built cross-class, interracial alliances – often along lines of female solidarity – with teachers and unionists to preserve and expand their roles in schools. Studying their work in classrooms challenges stories of decline and failure in the freedom struggle and the War on Poverty in the 1960s. Finally, the national influence of Harlem’s paraprofessional movement demonstrates the continued importance of Harlem as a laboratory and bellwether for the Black freedom struggle, and for the many campaigns for freedom and citizenship that this struggle continues to influence.

Parent-Teacher Teams in Harlem: An Introduction

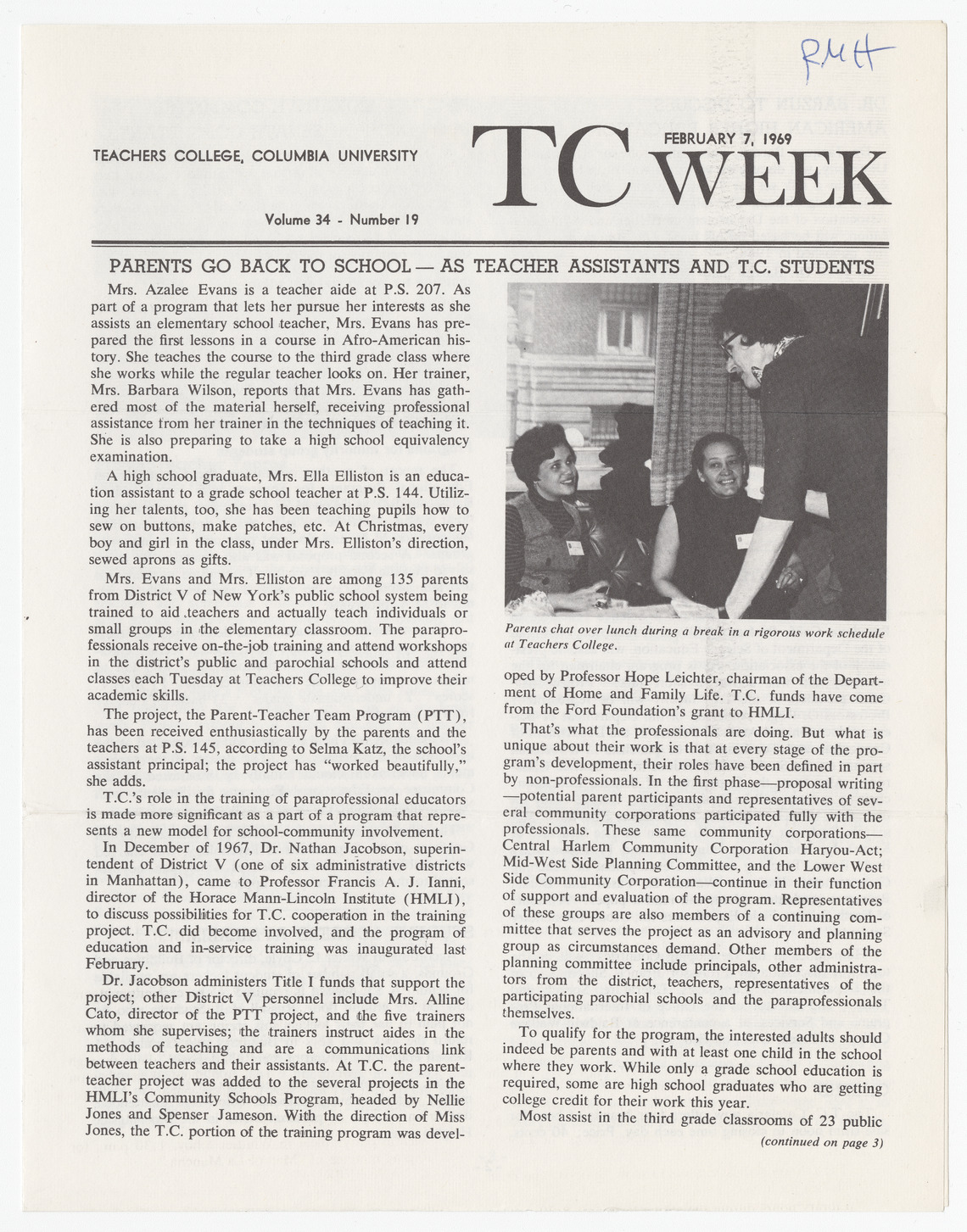

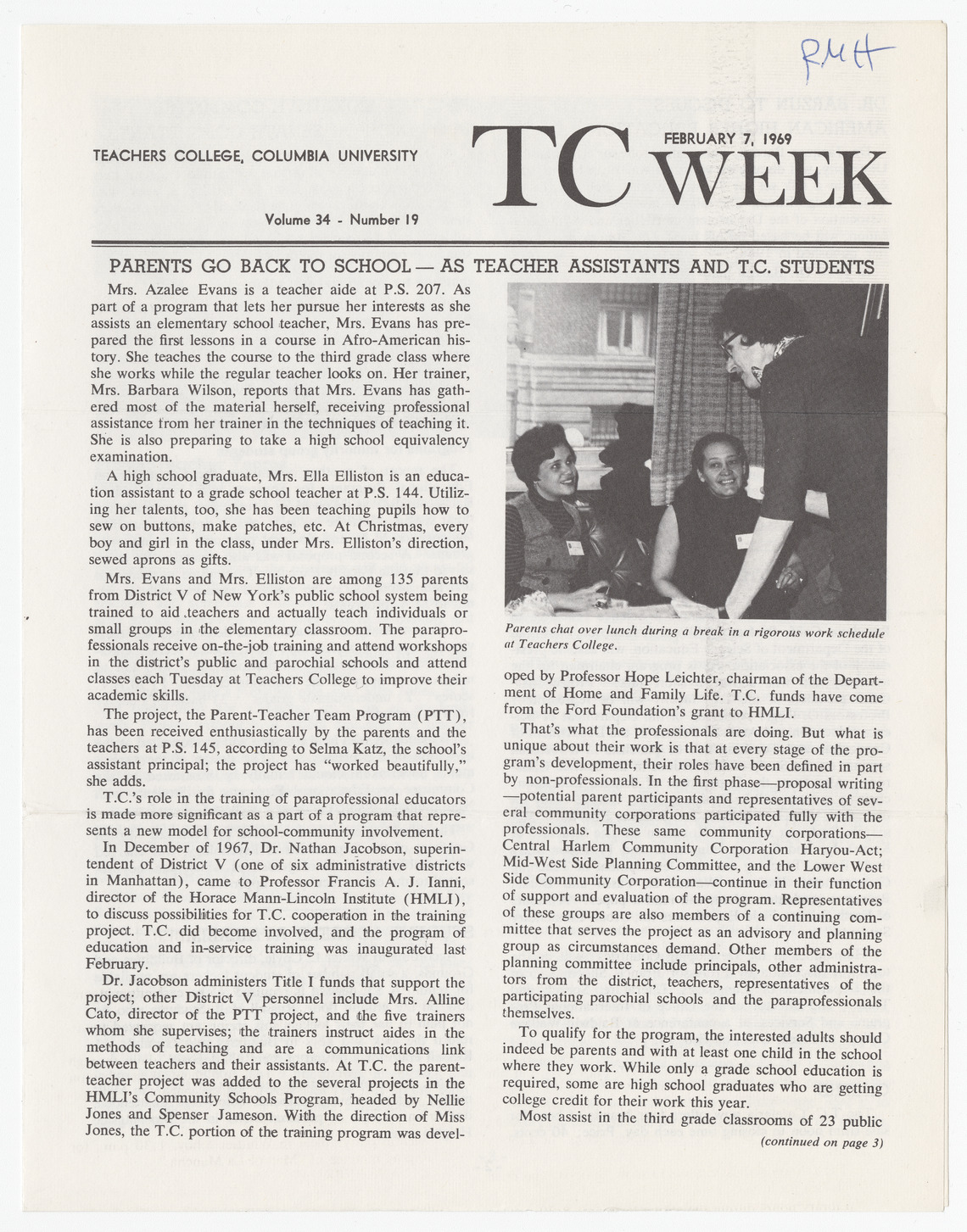

Above: TC Week

It "Worked Beautifully": Parent-Teacher Teams, February 1969

In the late 1960s, public education in New York City was in crisis. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Harlem, where a decade of parent-led civil rights organizing had done little to improve student achievement or desegregate the neighborhood’s overcrowded, crumbling schools. In 1968, an experimental program of “community control” that included a portion of Harlem and East Harlem had devolved into chaos when parent organizers and the teachers’ union clashed over the transfer of teachers. By the end of the year, distrust and hostility between students, parents, teacher and administrators was at an all-time high.

In the midst of this maelstrom, the newsletter of Teachers College, Columbia University ran a front-page report titled “Parents Go Back to School - As Teacher Assistants and TC Students.” Over the preceding year, TC had joined parents, teachers, community organizations, and the local school district in building a program called “Parent-Teacher Teams” in the schools of Harlem and the Upper West Side. TC’s role, as the article explained, was “the training of paraprofessional educators … as part of a program that represents a new model for school-community involvement.”

Above: TC Week

“A New Model for School-Community Involvement”

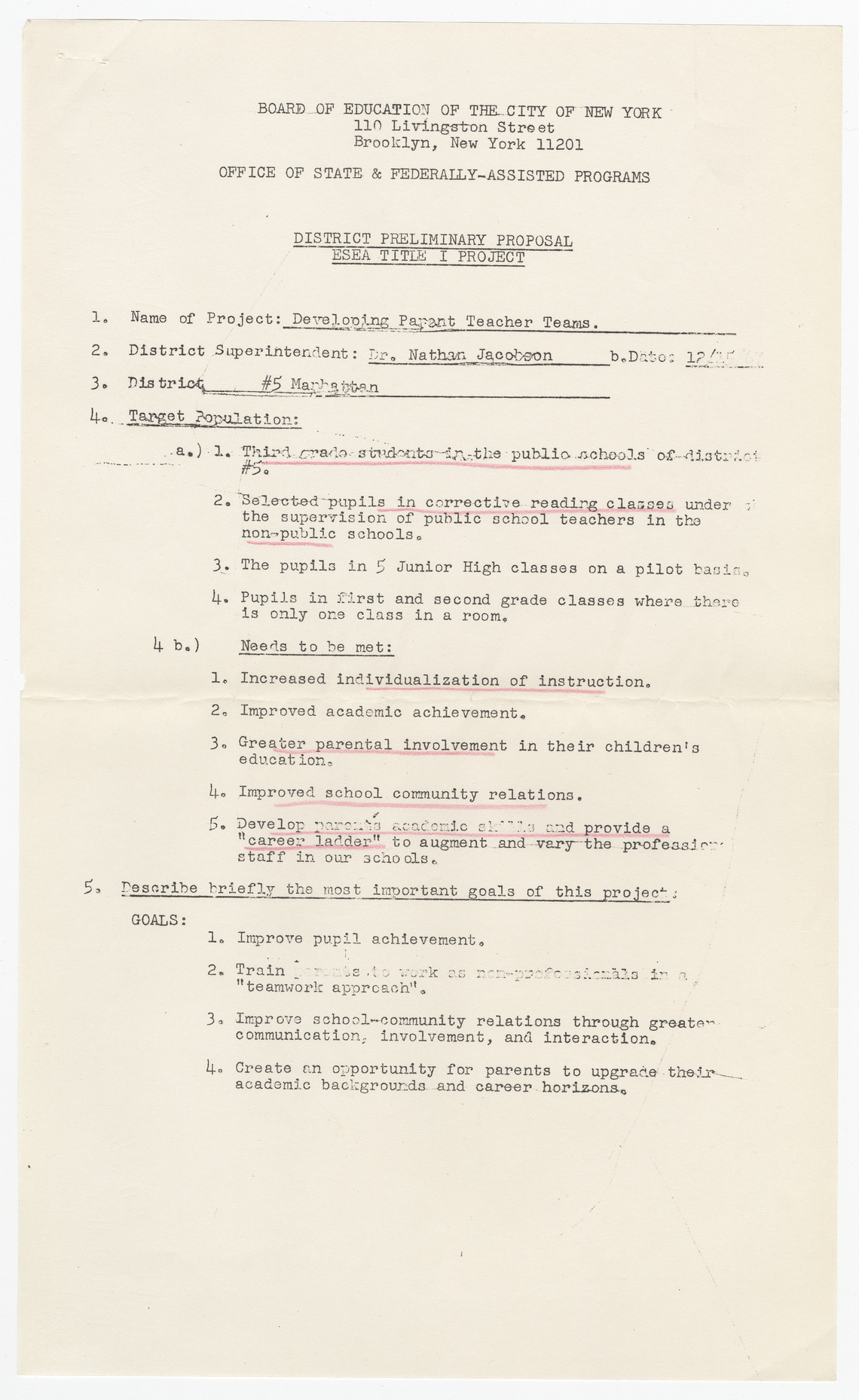

What was this new model? The school district’s project proposal from December of 1967 explained that parents would be trained to “work as non-professionals in a teamwork approach” with teachers in classrooms. The proposal cited three additional goals:

- "improve pupil achievement"

- "improve school-community relations through greater communication, involvement, and interaction"

"create an opportunity for parents to upgrade their academic backgrounds and career horizons" (and possibly to become fully-certified teachers themselves)

Educational scholars, activists, and administrators at the time would have recognized these three goals as the three pillars of the “New Careers” movement in antipoverty policy. The policy scholars who created the New Careers model had developed their ideas while working in community-based organizations in Harlem, the most influential of which was Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited, Inc (HARYOU). By the late 1960s, federal funds from the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Act provided new opportunities for local schools to put this vision into practice.

To achieve its three goals, the school district partnered with local community action agencies, including HARYOU, to recruit parents. They also created a twelve-member Parent Council, elected from among the participants, to help shape and govern the program. TC helped develop the training program for parent educators, which included sessions at schools and the college.

One year in, TC Week reported that Parent-Teacher Teams was exceeding expectations. Parent educators were teaching their students everything from African American history to the mending of clothing. One principal reported that the project had been “received enthusiastically by the parents and the teachers” and, in her own estimation, it “worked beautifully.” At TC, most parents worked toward high school diplomas, while those who had already graduated earned college credits. Reports from community organizations and the school district echoed TC Week’s assessment: Parent-Teacher Teams was improving instruction, facilitating school-community partnerships, and creating jobs and training opportunities for local residents.

Exploring Parent-Teacher Teams

This exhibit uses archival materials, oral histories, and maps to explore the remarkable history of the Parent-Teacher Teams program. The exhibit includes links to sources have many more stories to tell. They are provided here to allow readers, educators, and scholars to interact and create new narratives with them.

The exhibit tells a chronological story of Parent-Teacher Teams. It begins with the origins of paraprofessional programs in Harlem at the intersection of the Civil Rights Movement and the War on Poverty. From there, it traces the creation, evolution, and demise of this particular program, before reflecting on the wider trajectory of paraprofessional programs in education and their legacy. Moving through the exhibit in this way raises historical questions. How did programs employing parent educators come about? Who supported them, and why? How did parents and teachers work together in the classroom? Broadly, what does this example of parent-teacher cooperation - in a moment of tremendous conflict - reveal about public schools, freedom struggles, antipoverty policy, and urban governance in this era of Harlem’s history?

Maps included within the exhibit tell a geographic story of Parent-Teacher Teams. Parent-Teacher Teams, and programs like it, restructured the social and institutional geography of schooling and learning and Harlem. In doing so, they raised questions that are often best explored spatially. What relationship should schools and educators have with the students, parents, and neighborhoods they serve? How are wealth and power distributed within cities, and what can schools do to address these inequalities? How do people organize with one another to shape public education, economic opportunity, and urban politics?

At its height, Parent-Teacher Teams employed 130 local residents in 27 schools, where they served 3,900 students. The Program was one of hundreds in New York City, which employed 10,000 paraprofessional educators by 1970. In the three years that it operated, Parent-Teacher Teams received rave reviews from parents, teachers, and administrators, but it was shuttered in 1970 as New York City’s school system was restructured and the Ford Foundation and Columbia University ended their support for the project.

However, similar programs persisted in Harlem throughout the 1970s, and paraprofessional educators continue to work in public schools in many capacities. Exploring the Parent-Teacher Teams program does not offer simple solutions or portable models, but it does provide the opportunity to reflect on the possibilities and challenges for parent educators today.

Harlem: Cradle for New Careers

"Anything is Possible": Envisioning the Future of Schooling in Harlem, 1957-1967

Laura Pires-Hester, Social Worker at Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU) 1963-65:At HARYOU, there was kind of an atmosphere, an environment, of anything is possible. And, you know, the beginning of the sixties, that’s what, you know, the Kennedys … It was like “we can do anything.” We really believed the budget of $118 million … we believed that that would be forthcoming. [Laughing] We believed that that was going to make a major change.

Hope Leichter, Professor, Teachers College and Training Director for Parent-Teacher Teams, 1967-1970:So it was, you know, the era of the Great Society and … these weren’t empty words. Someone could go out and have an idea for how to create a more egalitarian society, create opportunities for those who wouldn’t have had them. And it wasn’t just like “oh, we’re going to work for equity and we’re going to have a benchmark of equity.” It wasn’t. I’m not saying it was all totally sincere - or ever is - but I’m saying it wasn’t unreal.

Laura Pires-Hester and Hope Leichter have known one another for nearly half a century. They met while working to build paraprofessional programs in New York City through an organization called the Women’s Talent Corps in the late 1960s. Their paths led both of them through Harlem, where they encountered the growing “urban crisis” - including an educational crisis in the overcrowded, dilapidated, segregated schools of the area - but also a groundswell of community-based activism in response to it. Interviewed recently, Pires-Hester and Leichter were clear-eyed about the challenges that students, parents, and activists faced, but both remained awed by the energy and commitment of Harlem’s activists in these years. It was this energy that produced some of the first demands for parent and early models for paraprofessional programs like Parent-Teacher Teams.

Postwar Educational Activism in Harlem: Seeking Community Involvement

Educational activism in Harlem dates back to the early twentieth century, but a combination of factors gave this organizing new urgency in the decades following the Second World War. These included the explosive growth of Harlem’s population during the Second Great Migration - leading to overcrowded schools - and the rise of the Civil Rights Movement in New York City.

The history of educational activism in New York City is most often told as a story of the failure of campaigns for school integration, which peaked with a one-day boycott of over 400,000 students in 1964. Following these campaigns, Black and Latino New Yorkers moved to seek community control of local schools, which culminated in clashes between parents and teachers in 1968. Throughout this period, however, educational activists in New York City fought for increased parent involvement and participation in school governance. Meeting with Mayor Robert F. Wagner in 1957, Harlem NAACP leader Ella Baker demanded not only the desegregation of Harlem’s schools but “the highest degree of democracy” in the city’s school system, to be facilitated through increased parent involvement. One avenue for involvement that Baker and other activists proposed was direct local hiring of parents to work in public schools, where their presence would serve to support students, inform teachers, and connect parents to the educational process.

While real ideological debates took place within and among civil rights organizations, a wide range of activists came to support local hiring by the early 1960s. Supporters of this vision included Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, who hoped such programs would desegregate the municipal workforce and open job opportunities; American Federation of Teachers Vice President Richard Parrish, who believed paraprofessional educators would improve teaching and help integrate the faculty; and radical social worker Preston Wilcox, who saw local hiring as a route to greater community participation, and ultimately community control, in public schooling. These organizers seized upon the chance to put their visions into action when the opportunity presented itself in the form of federal funds for community action.

![[Photo Standalone, No Title]](/img/derivatives/simple/jur013/fullwidth.jpg)

Above: [Photo Standalone, No Title]

Modeling Community Education at HARYOU

Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited, Inc (HARYOU), a federally-funded, community-based antipoverty organization that became a model for the War on Poverty, provided several early opportunities for parents and teachers to work together. Richard Parrish (pictured), a Harlem teacher who led the desegregation of the American Federation of Teachers in the 1950s, worked with HARYOU to hire parent educators to work with teachers in an afterschool program. The program was designed to give students the opportunity to “identify and associate with adequate role models on a more personal level” and encourage “parent and teacher cooperation.” By 1963, the program served 2,800 students at 10 Harlem schools and community centers. HARYOU’s “Committee on Education and the Schools” pressured district superintendents to hire parents in similar roles, and to focus their hiring on “welfare mothers,” who needed jobs that left room for childcare.

In 1964, HARYOU published a seminal report on their activities. Titled “Youth in the Ghetto: A Study of the Consequences of Powerlessness and a Blueprint for Change,” it not only diagnosed the challenges facing young Harlemites, but offered solutions. Among HARYOU’s “Ten Anticipated Needs” for Harlem’s youth was a direct call for parent educators:

“The youth of Harlem appear to be in need of parent aides or surrogates who would demand for them what middle-class parents demand and obtain for their children from schools and other social institutions. HARYOU should seek to provide machinery whereby community groups such as fraternities, sororities, social groups, PTAs, and churches assume the responsibility of this role. It would be important that the activities of these groups do not increase the dependency of the parents, but rather stimulate and motivate them to develop an increasing sense of their own power to affect desired change.”

Thanks in large part to the influence of HARYOU’s model programs, and the wide reach of “Youth in the Ghetto,” this was a call that came to be answered in the years to come.

Harlem's Influence: The Rise of the New Careers Movement

After reading a draft of “Youth in the Ghetto,” Laura Pires-Hester added an explanatory paragraph to the document. Her goal was to describe in detail the multiple benefits of hiring local residents to work with their neighbors:

"In a very real way, the use of indigenous nonprofessionals in staff positions is forced by the dearth of trained professionals. At the same time, however, the use of such persons grows out of concern for a tendency of professionals to 'flee from the client,' and for the difficulty of communication between persons of different backgrounds and outlooks. It is HARYOU's belief that the use of persons only 'one step removed' from the client will improve the giving of service as well as provide useful and meaningful employment for Harlem's residents."

When the report was published, Pires-Hester’s friend Frank Riessman, an influential social psychologist who worked with her at HARYOU, was taken with this paragraph. One year later, Riessman used it as the opening for his own policy manifesto, New Careers for the Poor: The Non-Professional in Human Services co-authored with Arthur Pearl. As Riessman explained:

This statement, take from the HARYOU proposal, forms the basis thesis of this book. Hiring the poor to serve the poor, is a fundamental approach to poverty in an automated age ... At the same time that it provides vastly improved service for those in need, this approach can also reduce the manpower crisis in health, education, and welfare fields.

Riessman’s book launched a “New Careers Movement” in antipoverty policy. In 1966, New York Congressman James H. Scheuer co-sponsored a “New Careers Amendment” to the Economic Opportunity Act (the principal act that funded War on Poverty programming) that directly funded such programs, including many in New York City. Federal officials in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), which administered the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), also pushed local school districts to use newly-allocated funding from the ESEA to hire locally. As this funding made its way back down the ladder of government into Harlem and other New York City communities, the same grassroots activists and local institutions that had inspired Riessman’s vision had the opportunity to put it into practice.

Creating Parent-Teacher Teams: Institutional Cooperation

The Many Sponsors of Parent-Teacher Teams

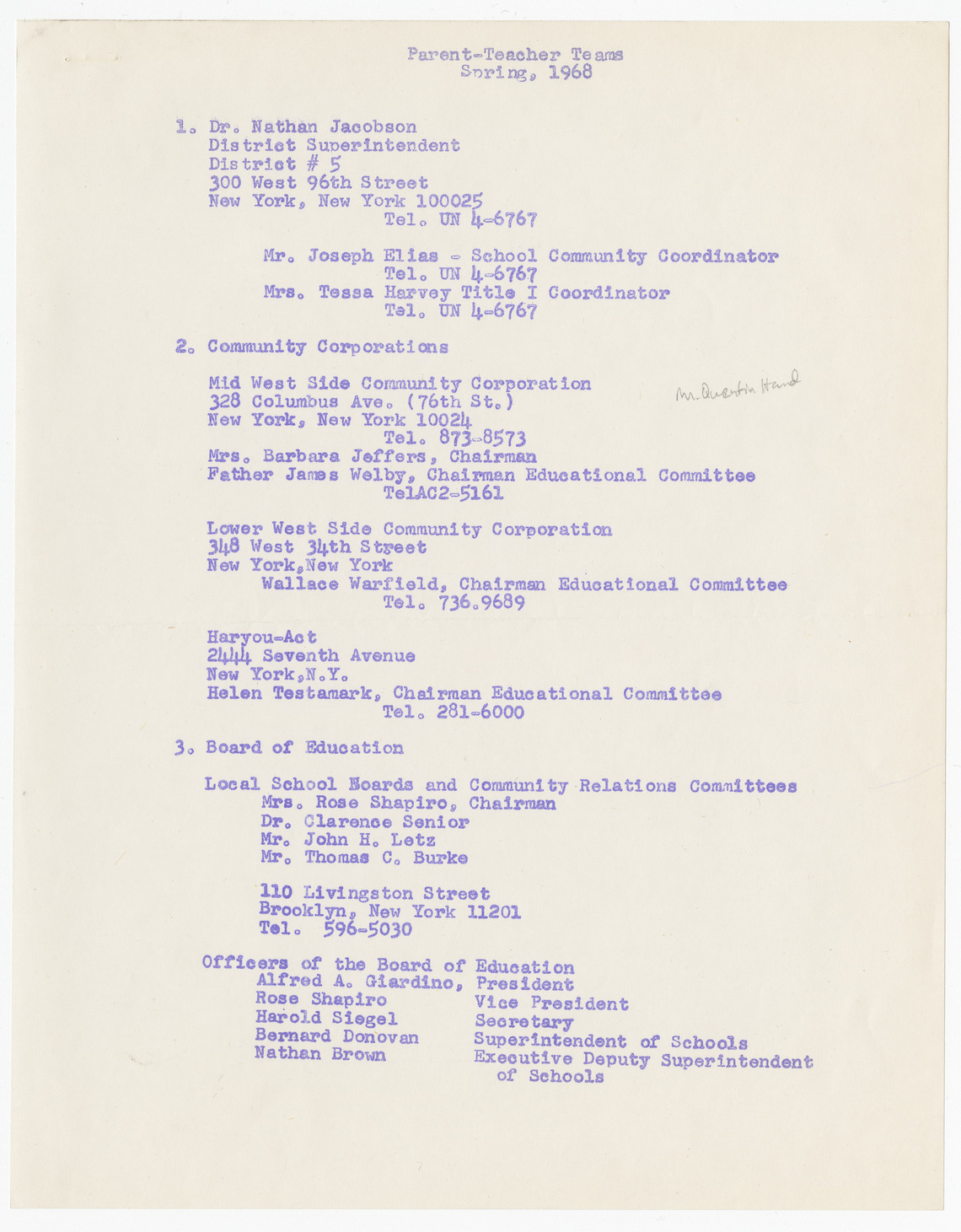

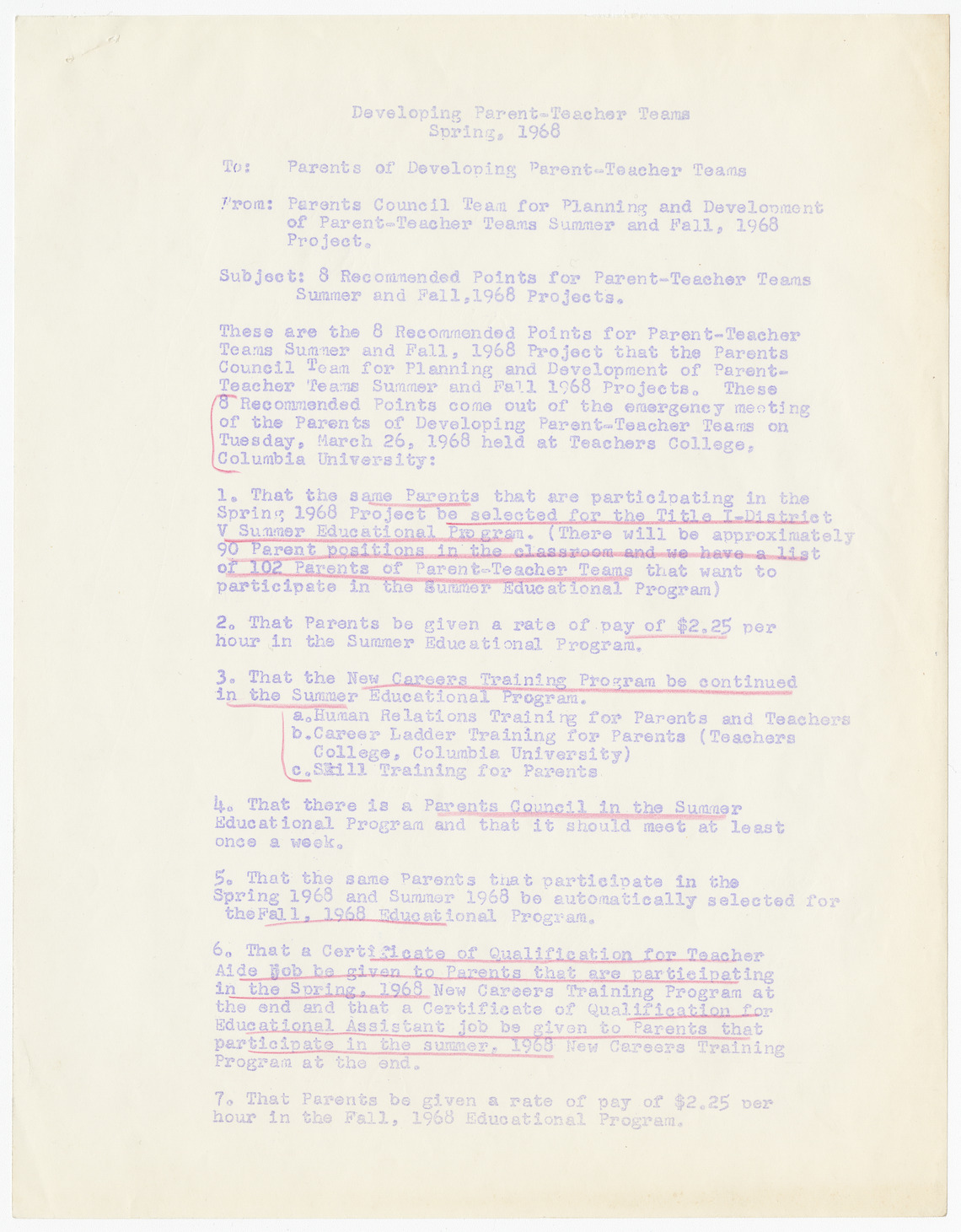

When Local School District 5 of the New York City Board of Education moved to create Parent-Teacher Teams in 1967, they took advantage of a rich landscape of organizations that were invested in improving public education through parent involvement and local hiring. An early document from the program (above) outlines these extensive partnerships:

The Educational Bureaucracy: Federal Funds to Local School Districts

In order to fund the program, District 5 applied to the city’s Central Board of Education for a grant. The $224,000 they received for the program’s first semester was drawn from the Board’s own allocation of resources from Title I of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) which dispersed $1.1 billion to address the educational needs of children living in poverty. The ESEA funded paraprofessional programs all across New York City in the nation in these years.

District 5 received roughly $600,000 of Title I funding for the 1968 school year. In order to better connect the District with the community, they also opened a storefront office on Columbus Avenue in April of that year (their main office was located in a public school building on 96th Street). This storefront served as the headquarters of Parent-Teacher Teams

Community Action Agencies

New York City’s Central Board of Education, acting on the recommendations of federal officials in the Office of Education, required city-recognized antipoverty organizations - known as Community Action Agencies, or CAAs - to play an active role in the planning and implementation of programs funded by Title I. When the Board officially began hiring paraprofessional educators in the fall of 1967, they created a formula for hiring: half of all “paras” would be hired at the discretion of principals and district administrators, but the other half would be selected for their positions by CAAs. HARYOU-ACT (created by a merger of HARYOU and another Harlem organization, Associated Community Teams, or ACT) worked with the District in this role, along with two other Upper West Side groups.

TC Week’s 1969 article singled out this commitment to community involvement. “What is unique about their work,” TC Week wrote of the TC staff and faculty involved in the program “is that at every stage of the program’s development, their roles have been defined in part by non-professionals.” In other words, parent voices shaped the way that TC and the District designed and administered Parent-Teacher Teams.

Elite Educational Institutions and Foundations

To provide academic training to parent educators, District 5 partnered with Teachers College, Columbia University. Teachers College, in turn, had received a $2.5 million grant from the Ford Foundation to run a series of programs, including an Urban Community Schools Project. TC provided an educational program for parent educators through this project in partnership with the Department of Home and Family Life, which was chaired by Hope Leichter.

In the 1960s, the Ford Foundation was one of the most active and influential philanthropic institutions in education. Ford funded hundreds of programs in New York City, most famously the “Demonstration Districts” in community control in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Harlem, and the Lower East Side. This experiment, which sparked the 1968 Teachers Strikes, took place at the same time as Parent-Teacher Teams and also sought to create parent involvement in public schooling, albeit with a different model.

The Plan: Goals for Parent-Teacher Teams

The proposal created by the District and its partners listed the following “Needs to be met” and “Goals” to describe the impact that they hoped Parent-Teacher Teams would have on their schools:

Needs to be met:

1. Increased individualization of instruction

2. Improved academic achievement

3. Greater parental involvement in their children’s education

4. Improved school community relations

5. Develop parents’ academic skills and provide a “career ladder” to augment and vary the professional staff in our schools.

Goals of the project:

1. Improve pupil achievement

2. Train parents to work as non-professionals in a “teamwork approach.”

3. Improve school-community relations through greater communication, involvement, and interaction.

4. Create an opportunity for parents to upgrade their academic backgrounds and career horizons.

The program advertised for parent applicants with “at least fifth grade literacy in English,” and “interest in working with children.” Using feminine pronouns, the proposal continued to describe the work paraprofessionals would do: “She should be willing to relate to children, teachers, and other parents. She should have the desire and ability to participate in an educational career program, after working hours, that will lead to a teaching career.” While the program was open to parents of any gender, only one father (of 130 parents) participated over the course of three years (across New York City in 1970, 93% of paras were women, and 80% were mothers). In a separate report, the District noted that the aim of the programs was “to provide additional teachers in the early reading grades and bilingual assistance for Spanish- and French-speaking children.” Parents would work 20 hours across four days every week, 16 in third-grade classrooms as teacher aides, and 4 at afterschool training sessions. Pay was set between $1.75 and $2.25 an hour, depending on educational credentials; the wages were, at the time, just slightly above the federal minimum wage. In addition, parents would have the opportunity to attend classes at TC after school and on their days off, for which they would receive a small additional stipend.

When this proposal was funded in December of 1967, the stage was set for Parent-Teacher Teams. What remained was for parents, teachers, and administrators to come together to make it happen.

Making Parent-Teacher Teams Work

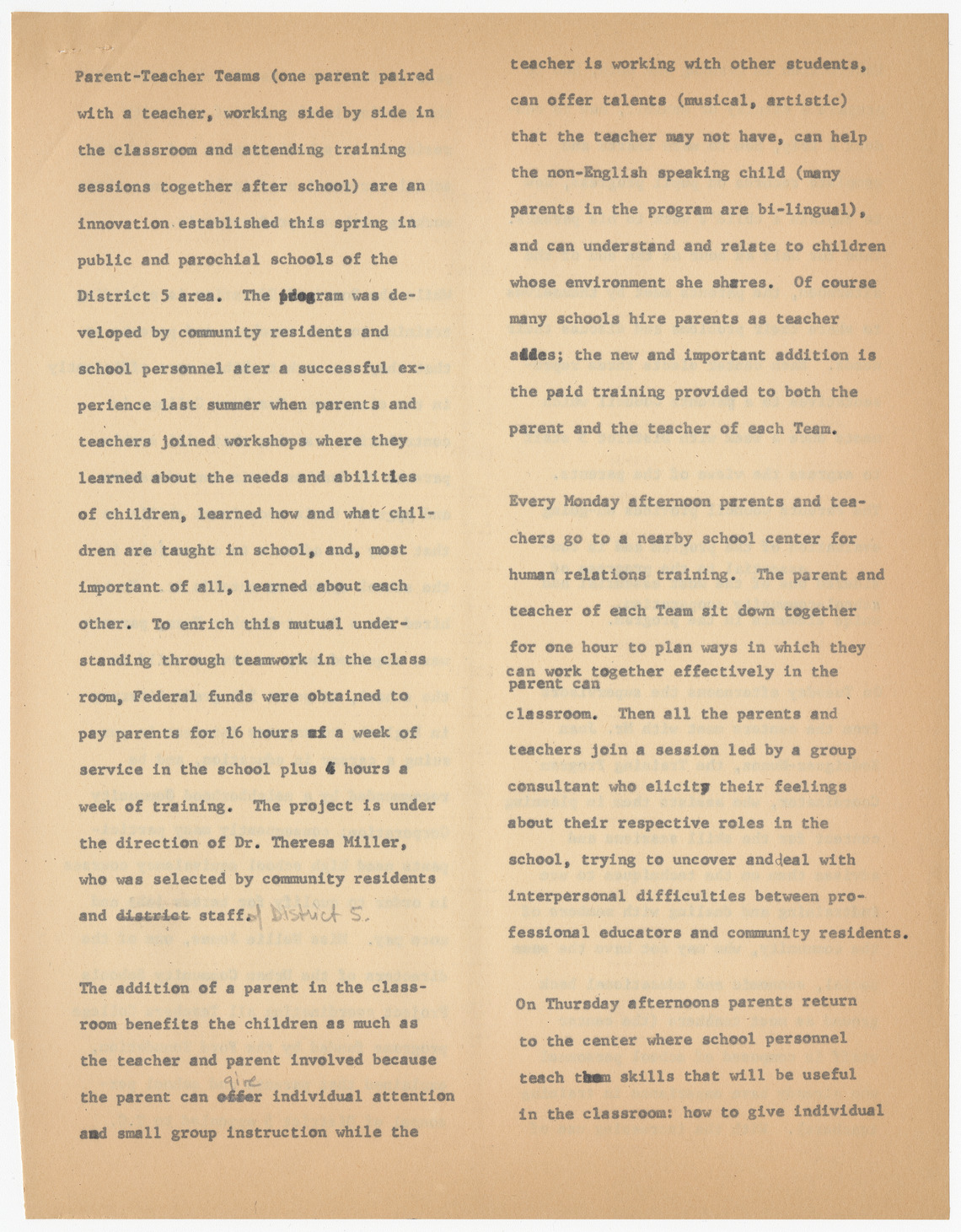

Building Mutual Understanding Between Parents and Teachers

District 5’s 1967 proposal for Parent-Teacher Teams was built, in part, on a preliminary program the district ran during the previous summer. On a volunteer basis, “parents and teachers joined workshops where they learned about the needs and abilities of children, learned how and what children are taught in school, and, most important of all, learned about each other.” The process, according to the report that documented it in the spring of 1968, generated “mutual understanding” that laid the groundwork for parent-teacher cooperation in the classroom. One teacher who took part in the program told the organizers:”Parents want the same thing that I want - each is looking out for the welfare of the child. I can’t wait to have a parent in my room.”

The New York Times sent reporter Olive Evans to observe these sessions in August of 1967, and she was impressed. In an article titled “Showing Parents How to Help,” Evans reported:

"The experiment ... drawing from Negro, Puerto Rican, and white middle class neighborhoods, sought to bring parents and teachers together as equals, in an alliance to improve education."

These meetings gave prospective parent educators the opportunity to get to know one another and share their experiences as parents. While the program was primarily designed to bridge differences of class, race, and urban geography between teachers and parents, it also helped facilitated organizing among parents of many different backgrounds. One parent told organizers that the experience had changed her opinion of fellow mothers: “I learned that all mothers care about their children - not just the white ones. I have become far less bigoted against those who are not of my race. I’ve grown to like people regardless of their color or economic background.”

Naomi Hill, the project director, affirmed these goals when she spoke to the Times. Stressing the need for “an open school system,” Hill explained: “If we give of ourselves so that they realize we are human, then the parents can open up. One mother interviewed by Evans for the Times concurred, telling her: “I used to be so afraid of the school. Now I know it is a friendly place.”

These summer sessions demonstrated the power of bringing parents and teachers together, and encouraged the District to develop Parent-Teacher Teams. They also shaped the training processes that the District and TC developed for parents and teachers, together.

Challenges to Teamwork

The success of paraprofessional programs in education was never a given, as the following two clips describe. Teacher Lee Farber, who worked in Brooklyn and Queens, notes that many teachers feared the hiring of paraprofessionals would undermine their jobs, while paraprofessional Shelvy Young-Abrams describes a teacher who wanted nothing to do with her when she first started.

Lee Farber (teacher, Brooklyn): The paras became part of the UFT. There was a division ... And many teachers, many regular teachers, were very unhappy about the para program because they felt that that was a stepping stone to getting rid of teachers. That the paras would take over the role of the teacher and that would eliminate the need for having teachers.

Shelvy Young-Abrams (para, Lower East Side): My first experience in a classroom with a teacher, her name was Mrs. Perlman, I'll never forget. I came into the classroom. She did not want me to have anything to do with the children. No matter what I tried to do, "I'll do it. I'll do it." I used to go home with headaches. I mean it made me sick. I just couldn't understand. I would be sitting in the back of the classroom. The kid couldn't even come over and ask me a question. She was very protective of that classroom. And that happened, must have been about six months, seven months. I got tired of it. I went to the principal. I said, "You know, I don't like the way I'm being treated. I'm here to help. If I can't work with the children, and the kids can't come to me that makes a bad relationship in the classroom. The children understand that there's something going on between the two of us. There's only one person in that classroom, you listen to me. But I'm here. Mrs. Young is here." So I had a conversation with the principal, and I said, "I'm here to assist a teacher. I mean come on." So we had a conversation. He explained to her why I was there, and we ended up having the best working relationship in that classroom.

Building Teamwork into Training

In order to maintain the “mutual understanding” that these preliminary sessions created, District 5 built parent-teacher conversations into the training process. As the preliminary proposal described it, one hour (of four) every week would be set aside: “To give these two people additional opportunity to structure viable role relationships, practices, and procedures in the classroom. This is quite important, since involving the parent at a higher level than the children contributes to the parent’s status and her creative involvement on a teamwork basis.”

In this respect, Parent-Teacher Teams was at the cutting edge of paraprofessional programs in these years. As local hiring expanded rapidly, many programs simply placed parent educators in classrooms and hoped for the best. Devoted training for paras was less common, and committed, paid, one-on-one time between paras and teachers was rare. However, as a study conducted at New York Ciy’s Bank Street College of Education showed in 1968, such training seemed to make a significant impact on the functioning of paraprofessional programs. By devoting time to parent-teacher cooperation beyond the classroom, Parent-Teacher Teams aimed to maximize its impact in the classroom.

Mapping Parent-Teacher Teams

Reshaping the Social Geography of Schooling

Parent-Teacher Teams was one of thousands of programs created across the nation in the late 1960s to employ local parents in public schools as paraprofessional educators. This paraprofessional movement" was, in many ways, a response to geographic segregation and spatial inequality in American cities, which sorted people by race and class at many levels. Discriminatory policies and practices in real estate segregated residential neighborhoods and housing across and within metropolitan areas, separating many educators from the schools and neighborhoods where they worked. Coupled with administrative decisions about school zoning, these policies segregated schools in New York City. Residential and administrative segregation also limited the political power of working-class Black and Latinx New Yorkers. Discriminatory hiring policies segregated the teaching corps; when Parent-Teacher Teams began, 91% of teachers and 97% of administrators in New York City were white, while 58% of the student body was not. Public and private discrimination also segregated the workforce more broadly, both by directly preventing Black and Latinx New Yorkers from being hired or promoted, and by shifting jobs from the center of the city to the suburbs and from the Northeastern United States to the South and West. In several crucial respects, the goals of paraprofessional programs like Parent-Teacher Teams were spatial. Parent educators acted as conduits between schools and communities; the brought local knowledge and culture into schools to improve instruction and connect teachers and students, while explaining official policies and projects to skeptical parents. Hiring local parents desegregated the faculty, while their presence in classrooms and on the Parent Council included parents in educational decision-making and the political process. Jobs and training, meanwhile, provided economic stability and educational opportunity for parents in neighborhoods where both were increasingly scarce.

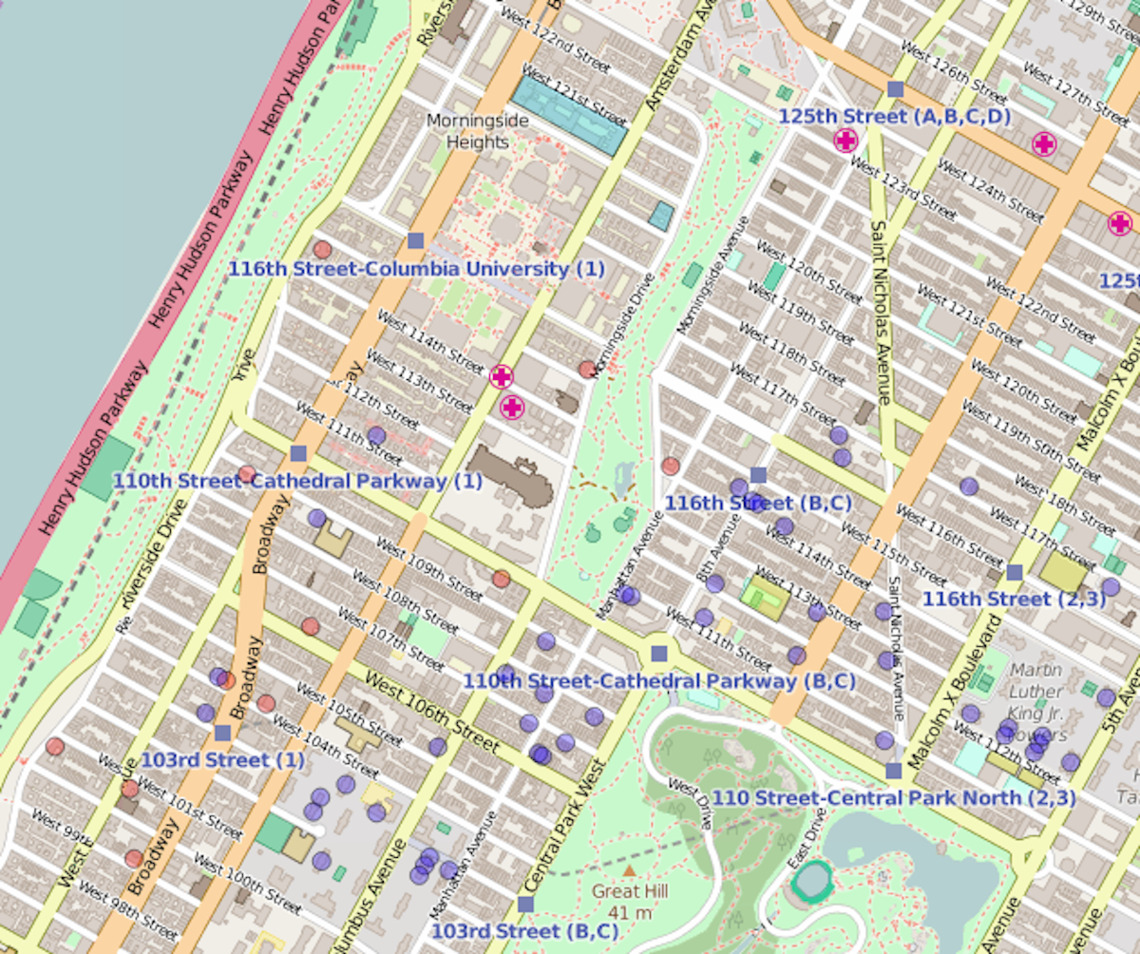

Exploring Parent-Teacher Teams through Mapping

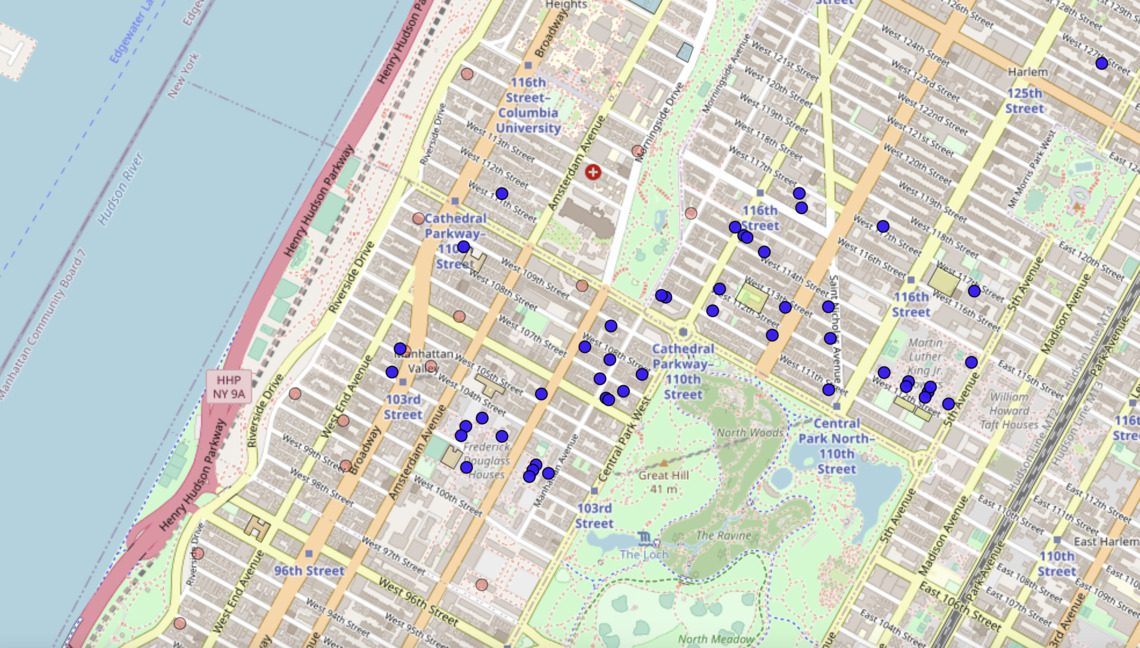

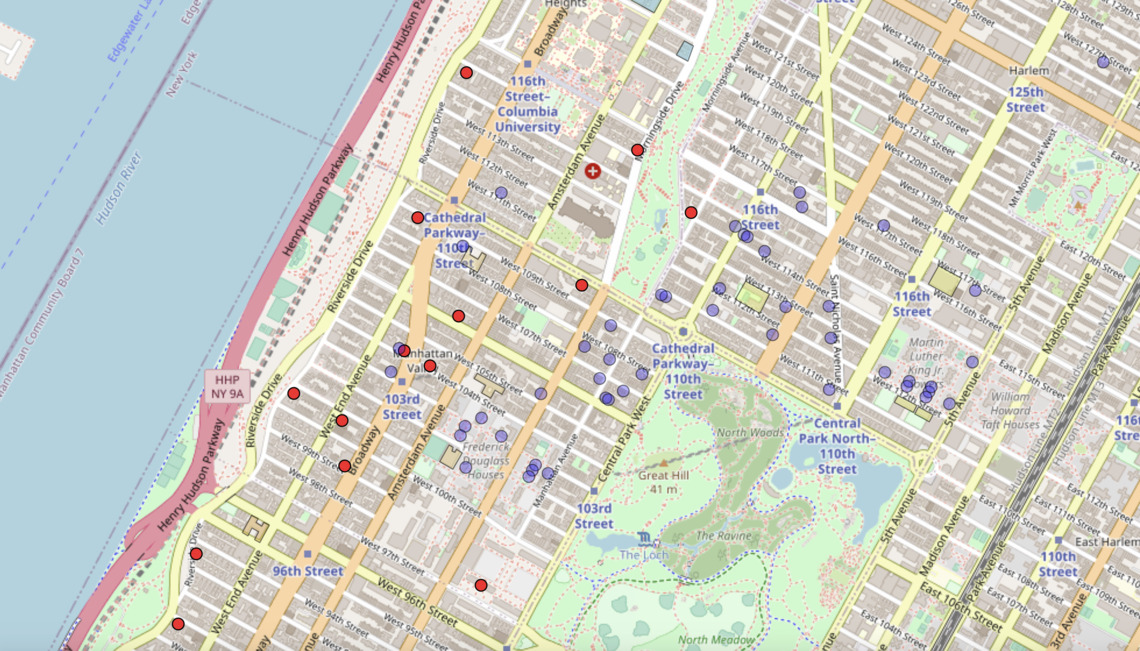

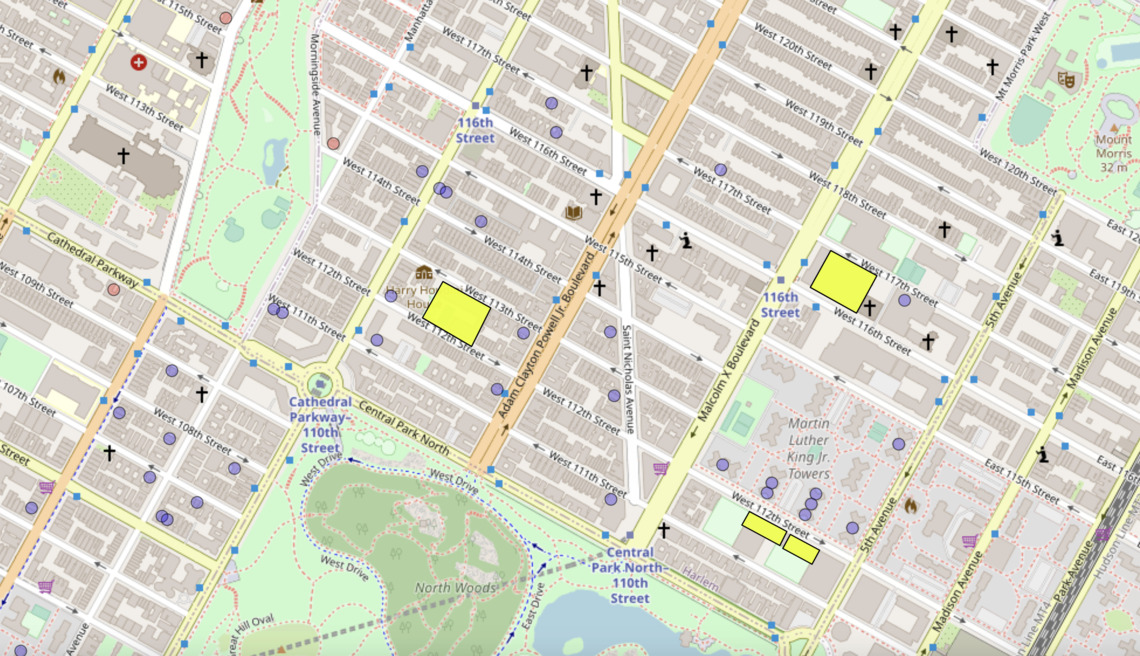

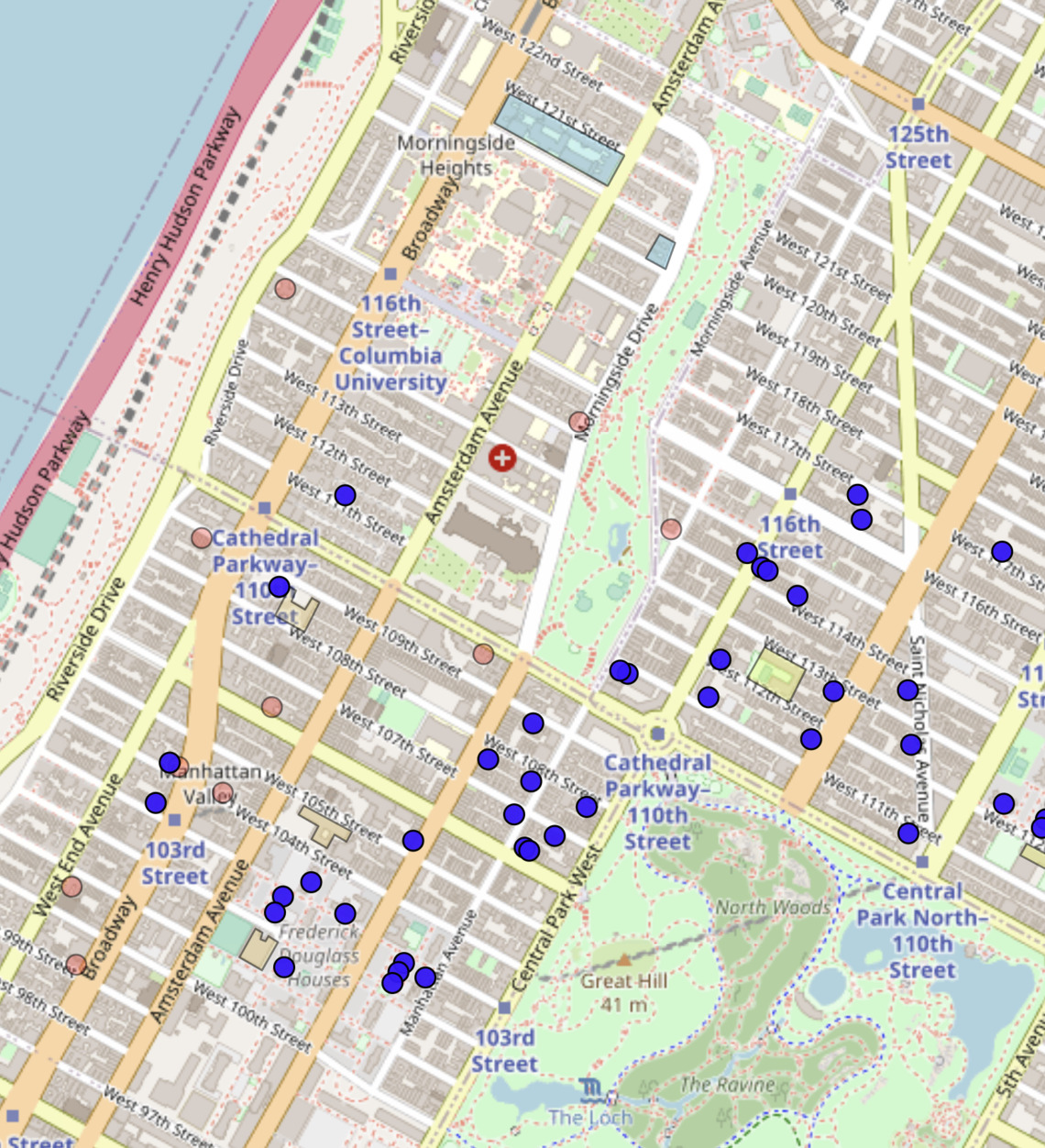

Mapping the people and institutions that participated in Parent-Teacher Teams helps to visualize and explore the ways in which this program reshaped social and institutional geographies of schooling and learning in Harlem and on the Upper West Side. The maps that follow use the home addresses of 47 parent educators (in blue) and 47 teachers (in red) who worked together in third-grade classrooms in seven schools (in yellow). Parents, teachers, and schools were organized into two "Centers" for administrative and training purposes: Center B, in South Harlem, and Center C, in the neighborhoods of Morningside Heights and Manhattan Valley, part of Manhattan's Upper West Side. The map also depicts District 5's two offices (in orange), Teachers College (in light blue) and Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited - Associated Community Teams (HARYOU-ACT), a local community action agency that helped select and train parent educators in Harlem (in green). How were all of these people and places located in relation to one another, and how did these relationships impact schooling and learning? While the dots on this map are static, viewers are asked to remember that these people were in motion. Parents and teachers moved from their homes to their schools, and moved around their neighborhoods to shop, worship, and socialize. In the context of the program, parents and teachers meet together at schools for professional development workshops, attended Parent Council meetings at District Offices, and traveled to Teachers College for high school and college classes. How did this program, and the movement of people through it, shape new kinds of schooling and learning processes in Harlem and on the Upper West Side?On the Map

Each blue dot represents the home address of one of 47 mothers hired to work as paraprofessional educators in the seven schools on this map. Parent educators lived very close to the schools where they worked, often within a few blocks, and saw their students and their parents regularly outside of the classroom, in supermarkets, parks, and places of worship. Parent educators were intimately familiar with their neighborhoods and brought local knowledge into schools. Once employed, they carried understandings of official policies and practices with them into formal and informal conversations with students, parents, and community members beyond schools. Thus, these dots represent community connections to schools and nodes of outreach for schools. Each dot also represents a new job and new training opportunities for a working mother.

Each red dot represents the home address of one of 47 participating teachers. Scattered across the metropolitan area, these dots illustrate the suburbanization of the teaching workforce in the 1960s. However, many participating teachers lived on the Upper West Side, some walking distance from the schools where they worked. This may have been on account of teacher self-selection: it would have been easier for teachers living nearby to participate in a program that demanded significant after-school training commitments. Teachers living in close proximity to their schools may also have been more sensitive to the need to connect to local communities. At the same time, only one teacher lived east of Morningside Park, and those who lived on the Upper West Side typically lived west of Amsterdam Avenue. Comparing the home addresses of teachers and parent educators reveals local patternings of class and race at several scales.

Center B was an administrative cluster of four schools in southern Harlem: PS 113, PS 184, PS 185, and PS 208. 26 of 27 parent educators working in these schools lived within a square quarter-mile bounded by Central Park, 117th Street, 5th Avenue, and Manhattan Avenue, while only one teacher did. In Harlem, the effects of long-running neighborhood-level segregation are visible in the distance between teachers and their workplaces. As one report explained, employing a parent-educators who can understand and relate to children whose environment she shares was meant to bridge this distance.

Center C was an administrative cluster of three schools in Morningside Heights and Manhattan Valley: PS 145, PS 165, and PS 179. All 21 parent educators lived within a few blocks of their schools, but so did many teachers, with some parents and teachers living on the same blocks and, in one instance, in the same building (on 104th Street). Spatial inequality is still present in this neighborhood; most parent addresses are clustered to the east, on the borders of Harlem and down the hill from more elite addresses on Broadway and Riverside Drive. Eight parent educators lived in public housing, while no teachers did. However, boundaries are more uneven in this cluster of schools, and the presence of parent addresses west of Amsterdam Avenue reveal that parents in Parent-Teacher Teams were not a homogeneous group, but came from many racial, ethnic, and class backgrounds.

Parent-Teacher Teams was administered by the New York City Board of Education's Local School District 5, which was headquartered in a school building on 96th Street. The District's boundaries stretched roughly from 59th Street to 125th Street on the Upper West Side and Harlem. The district opened a storefront office in 1968, shortly after Parent-Teacher Teams began, to better connect with parents and community members in the district. While it was more accessible than District 5's Headquarters, the storefront office remained at a distance from Harlem. HARYOU-ACT was a pioneering antipoverty organization founded with federal funding in 1962. HARYOU coordinated the use of parent educators as teacher aides in afterschool programs in Harlem and called for parents to be hired as teacher aides in local schools in their 1964 report, "Youth in the Ghetto." When the Board of Education authorized the hiring of paraprofessionals in 1967, they required Local School Districts to work with city-recognized Community Action Agencies (CAAs) in planning programs and hiring parents. HARYOU-ACT played this role for Parent-Teacher Teams in Harlem, recommending half of the parents who were hired. Though their offices were at 142nd Street and 7th Avenue, HARYOU-ACT ran programs for young people throughout the neighborhood. Teachers College is one of the oldest and most prestigious schools of education in the nation. Historically an elite institution, TC opened its doors to parent educators from Parent-Teacher Teams in 1968, at a time when Columbia University was locked in a bitter fight with Harlem residents over the construction of a new gymnasium in Morningside Park. Parents took high school and college classes at TC, and gained access to its library and recreational facilities for their families. TC training director Hope Leichter remembers this process as "more democratic than we could have planned, in that it helped break down barriers between the institution and its surrounding community. Morningside Heights, Incorporated, a community development organization founded by Columbia University in 1947, reported on the Parent-Teacher Teams program to the University, the Board of Education, and the wider public. They also kept a record of its progress. All of the archival materials used to produce this exhibit are housed in the collections of the Morningside Area Alliance in the Columbia University Archives, whose finding aid describes the organization as follows: Morningside Area Alliance was founded as Morningside Heights Inc. in 1947, out of the recommendations of two Columbia University-instituted committees. By the end of 1948 Morningside Heights Inc. made the decision to work towards neighborhood improvements by focusing on developing public housing and improving public schools. In addition the organization's housing-improvement mission, it was decided that Morningside Heights Inc. would act as a "clearing house" for all real estate purchases and transactions by the sponsoring institutions. To aid in this task, the stock corporation Remedco was founded in 1949 to act as the real estate arm of Morningside Heights Inc. The next largest area of Morningside Heights Inc. work was aid to public schools and programs for Morningside youth. The organization funded a music program in PS 125 and PS 165 from 1954-1958, and advocated for years on behalf of the effort to build another elementary school in Morningside Heights. Throughout its existence Morningside Heights Inc. worked to revitalize organized extracurricular youth activities in the neighborhood as part of a program intended to minimize the perceived causes of juvenile crime.

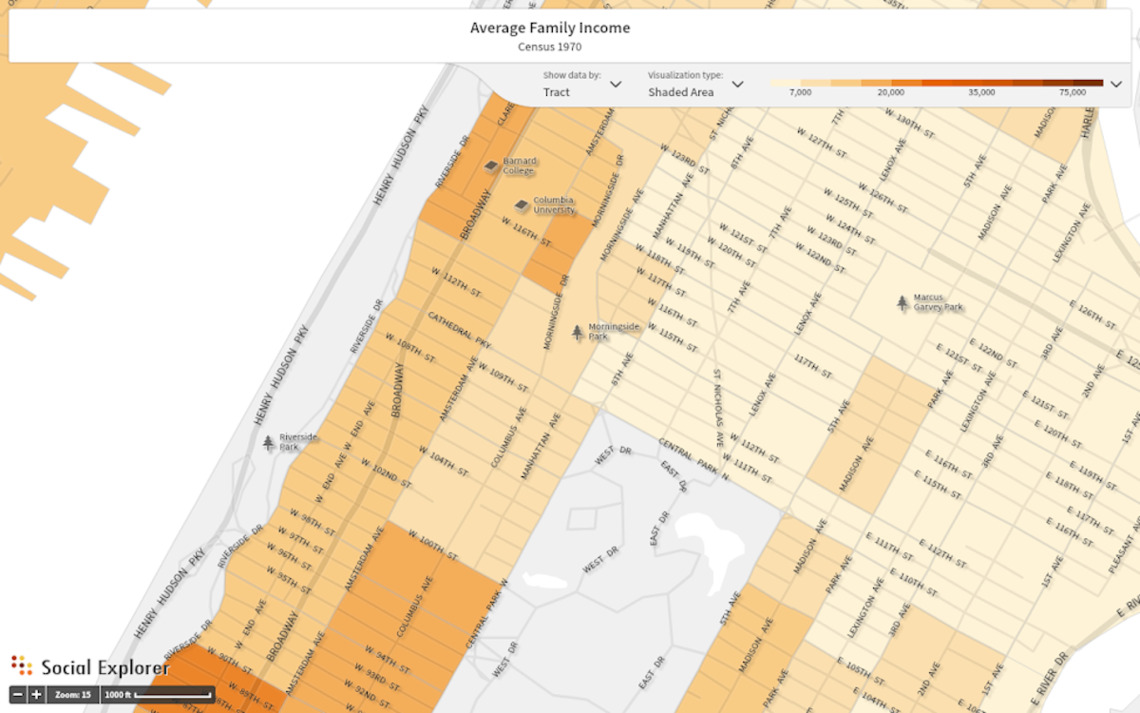

Mapping Harlem and the Upper West Side, 1970

The following maps were made using the data visualization tool Social Explorer. They chart the racial, economic, and educational landscape of Harlem and the Upper West Side, using data from the 1970 US Census. Mapping Race: Orange dots represent 10 black residents, green dots represent 10 white residents.

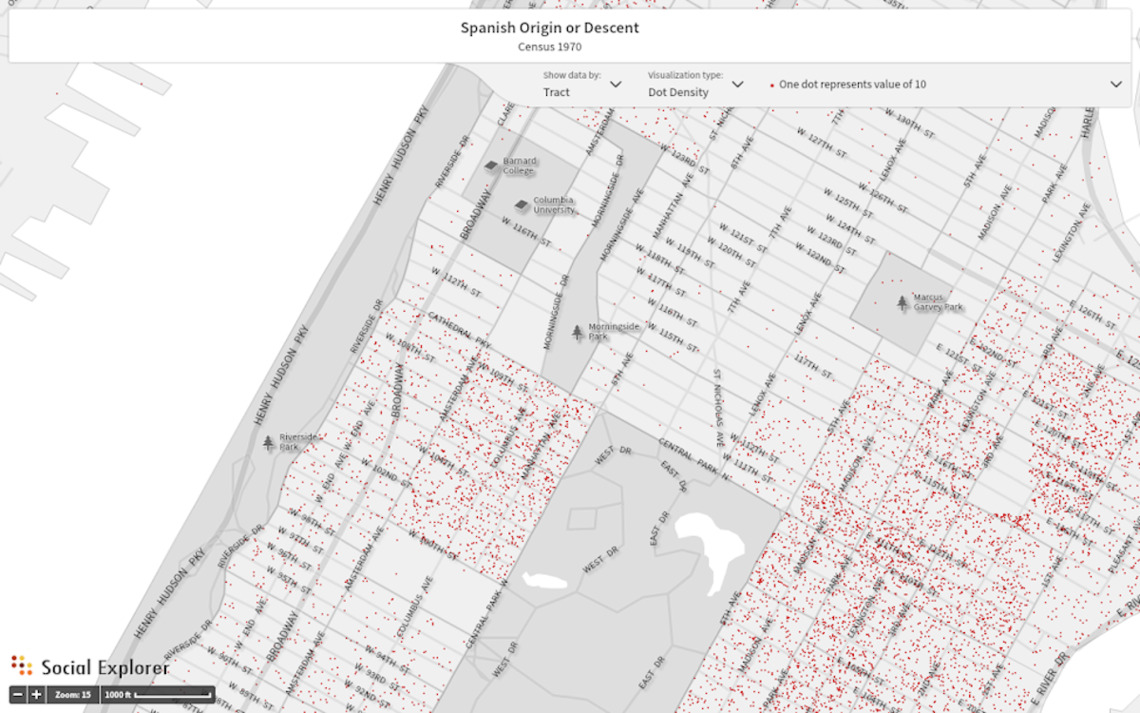

Race and Language: Each red dot represents 10 residents of "Spanish origin or descent"

Mapping Income: The ligher the census tract, the lower the average family income in that tract.

Above: Harlem Family Income, 1970

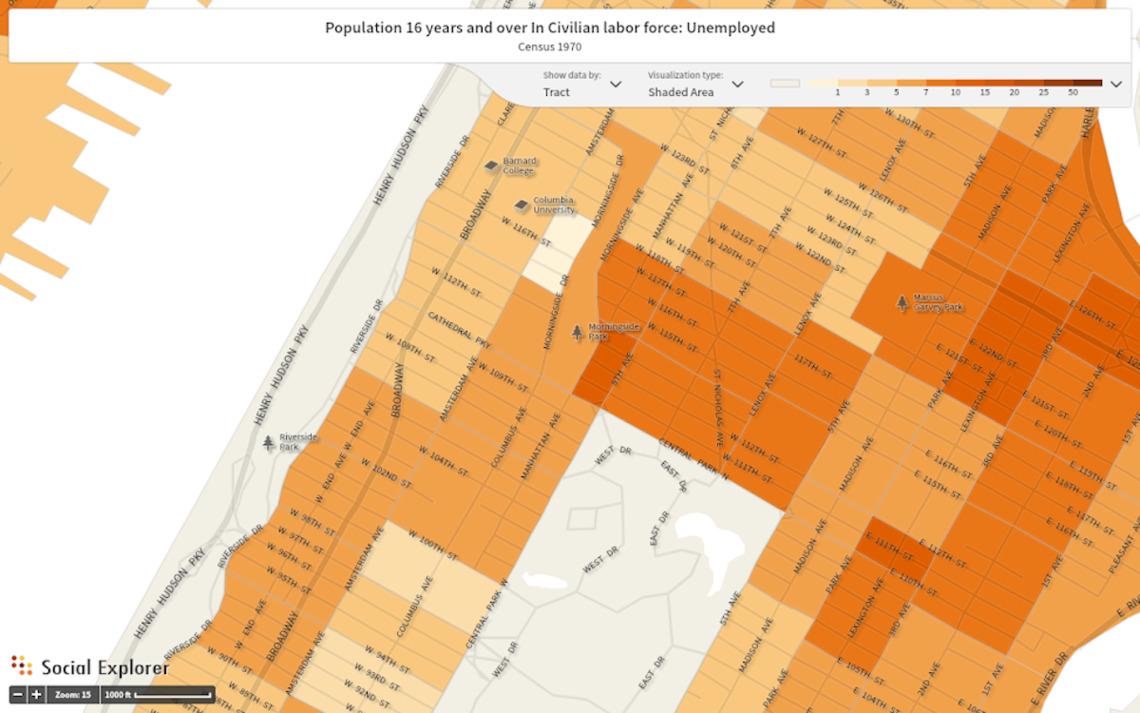

Mapping Unemployment: The darker the census tract, the higher the unemployment level in that tract.

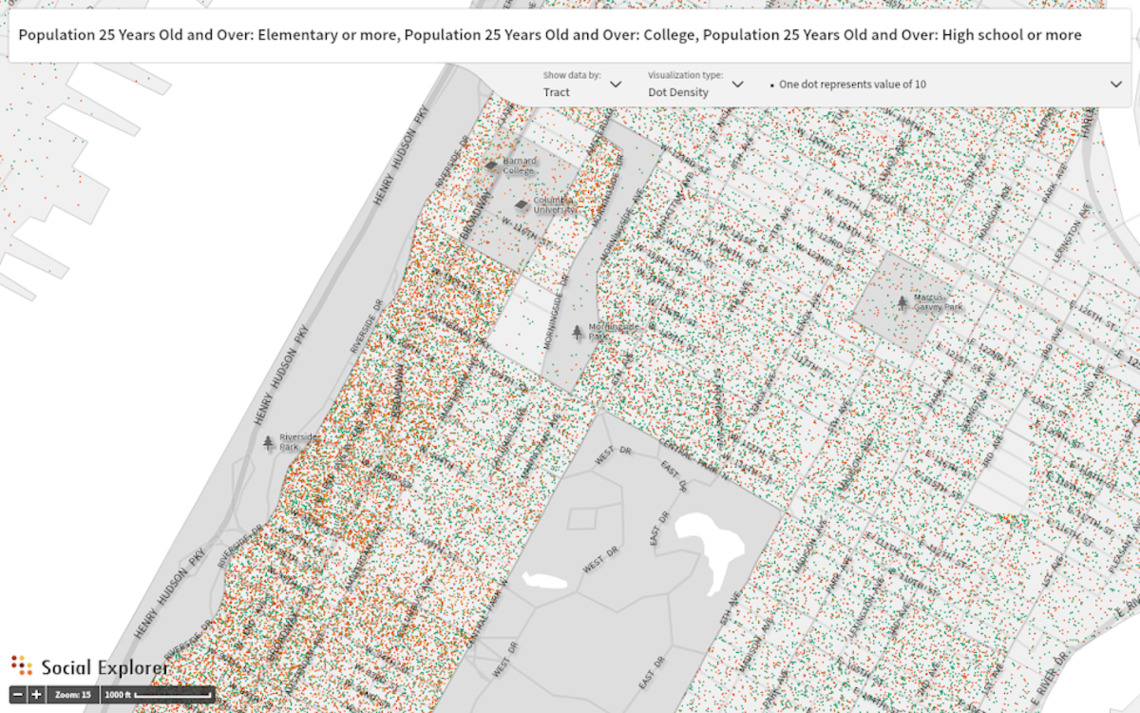

Mapping Educational Attainment: Green dots represent residents with an elementary education, orange dots represent those with high school diplomas, and red dots represent those with college diplomas (each dot represents 10 persons).

Impact: In the Classroom

Above: TC Week

The article published in TC Week in 1969 begins by describing the academic impact made by two parent educators. Mrs. Azalee Evans at PS 207 "has prepared the first lessons in a course on Afro-American history. She teaches the course to the third grade class where she works while the regular teacher looks on." Mrs. Ella Elliston, who also served on the program's Parent Council, "has been teaching pupils how to sew on buttons, make patches, etc. At Christmas, every boy and girl in the class, under Mrs. Elliston’s direction, sewed aprons as gifts.” An undated report from the files of Morningside Heights, Inc. that appears to have been written in 1968 confirms this positive assessment. Describing the work of parent educators, it notes: “The addition of a parent in the classroom benefits the children as much as the teacher and parent involved because the parent can give individual attention and small group instruction while the teacher is working with other students, can offer talents (musical, artistic) that the teacher may not have, can help the non-English speaking children (many parents in the program are bi-lingual) and can understand and relate to children whose environment she shares.” The initial proposal for Parent-Teacher Teams included a long list of proposed duties for parent educators. These ranged from providing individual assistance and small group work with students in classrooms to more specific directives, including

- "contribute to enrichment actvities by utilizing her special talents,"

-"to alert the teacher to the special needs of individual children,"

- "to give special encouragement and aid to the non-English speaking child," and

- "to be a source of affection and security to the children."

These duties range remarkably, from straight-ahead instructional assistance to emotional labor in support of children who might not otherwise receive it. They also suggest that parent educators might well transform the educational experience for students and teachers. As the reports from TC Week and Morningside Heights, Inc indicate, parent educators made the most of these opportunities, and administrators took note.

In addition to the specific impact of parent interventions, the presence and labor of parent educators in classrooms shifted the overall relationship between parents and teachers, and schools and communities. The lessons taught by Mrs. Evans and Mrs. Elliston did not just impart relevant knowledge, but validated community history and the practical skills of working women as educationally legitimate. The presence of parents speaking Spanish and French to Puerto Rican and Haitian students likewise validated their languages and cultures. Finally, the presence of educators with everyday connections to students and their parents in classrooms allowed teachers to better understand the particular, individual struggles of students, and made students more at home in schools.

The video shown above includes descriptions of paraprofessionals working with students in individual, small-group, and bilingual instruction.

Impact: Communication and Participation

Community Connections at Many Levels

Communication between parents and teachers - and at a broader level, schools and communities - developed in several ways with the structure of the Parent-Teacher Teams program. Some of these connections took place in individual classrooms, where parent educators used their knowledge of neighborhood and family life in Harlem to make students feel at home in school, and to inform teachers about particular needs or challenges that a student might face. Parent-teacher conversations were also built into the training process, which allocated one hour every week for teachers and parent educators to meet face-to-face. At the neighborhood level, parent educators moving between their homes, schools, churches, parks, and supermarkets carried information with them in both directions, keeping fellow parents appraised of what was happening in schools and informing teachers and administrators about the changing conditions of life in Harlem. In the following clip, Shelvy Young-Abrams describes her own place in the community where she worked and how her social position made her effective as an educator.

Shelvy Young-Abrams: It was great because you have to understand, I lived in the community with them. When we shopped, we saw each other at the stores, so I had a very good rapport with the parents, the kids, the community at that time, you know. That's when you had local school boards, and they wanted their turf, they wanted this. But I had a very good working relationship with everybody, you know. Parents would come to me and ask me questions, or you know, if I say, "We're having a PTA meeting, would you come?" As a matter of fact, I was a PTA president at one point. I started as a PTA president, and that also helped. So I was fighting also for parents' rights and everything else, and I was one of the ones [to] say, "I've been there, and this is how you do X, Y, and Z."

The Parent Council: Highlighting Parent and Paraprofessional Needs

Parent-Teacher Teams was also designed to include a formal organ for parent participation in public schooling, the 12-member parent council. Officially, this council was intended to "advise" the District on the shape of the program, but what power parents had in this capacity was undefined. However, for many parents and community organizers, programs like Parent-Teacher Teams provided a platform from which to challenge authority figures. Mary Dowery, a social worker who started her career in Harlem (at the Salvation Army) before moving to work with paraprofessional educators on the Lower East Side, remembered this process of empowerment in an interview. As she put it, programs like those developed at HARYOU and Mobilization for Youth taught parents "how to confront authority figures. Don't be afraid, don't be intimidated. Be respectful and courteous, but don't take any crap!" Early on, in the spring of 1968, the council gathered and issued an emergency statement. Their list of demands included better wages, job security, and formal certificates to acknowledge their participation in training. In the short term, it appears that the program was able to meet at least some of these demands, hiring paraprofessionals back for the summer and fall programs. Ultimately this trio of issues became rallying points for paraprofessionals across the city as they organized with the United Federation of Teachers, New York City's Teacher's Union, in 1969 and 1970. As discussed later in this exhibit, the combination of grants that funded programs like Parent-Teacher Teams often proved unstable. Making paraprofessional jobs permanent required citywide organizing.Empowering Parents in Bureaucratic Settings

Below, Mary Dowery, the professional social worker who led the program that employed these educators (pictured second from left), discusses the ways that parent educator programs encouraged people to stand up for themselves to authority figures. As evidenced by the demands listed by Parent-Teacher Teams, above, the experience of coming together empowered parents to advocate for their needs and the needs of their communities. Like Laura Pires-Hester and Hope Leichter (both of whom she worked with and knew), Dowery's path led her through Harlem, where she worked as a social worker for the Salvation Army in the 1950s.

Mary Dowery (social worker): Oh yeah, I trained them to go into homes and we did role playing. You know, the picture I showed you of Frank Riessman, and that was teaching these people how to do role playing. That’s what that session was about. With the, with the families, you know, how to confront authorities, authority figures. Don’t be afraid, don’t be intimidated. Be respectful and courteous but don’t take any crap!

Impact: Jobs and Careers

New Careers & New Kinds of Training

Community-based paraprofessional educators made an immediate impact on classrooms and communities, as the previous pages indicate. In addition to their day-to-day work, many paras sought the opportunity to become career educators, either in their current roles or as teachers. This was a central component of the "New Careers" vision, but it required both a significant commitment to creating new paths to teacher training and the allocation of resources to train and support paras on their educational journeys. While Parent-Teacher Teams did not last long enough to offer much more than high school equivalency degrees to its parent-educators, the program's directors and supporters at Teachers College worked hard to imagine these "new careers" and took steps toward realizing them in the three years that the program was operational.

Two Kinds of Training: Professional Development and Career Advancement

Parent-Teacher Teams paid parent educators and teachers to participate in four hours of training each week. Parent educators also received a stipend to attend classes at Teachers College for one day a week. District 5 and TC divided the tasks: the District trained “teachers and parents so that they can work together more efficiently in the classroom” while TC’s courses were designed to “enable parents to further their own education and upgrade their vocational skills so that they can advance to other jobs in the school system or outside it.” While the training was designed and implemented by professional educators at the District at TC, parent educators quickly became active participants in shaping this process and its implications for their own advancement and their roles in schools.

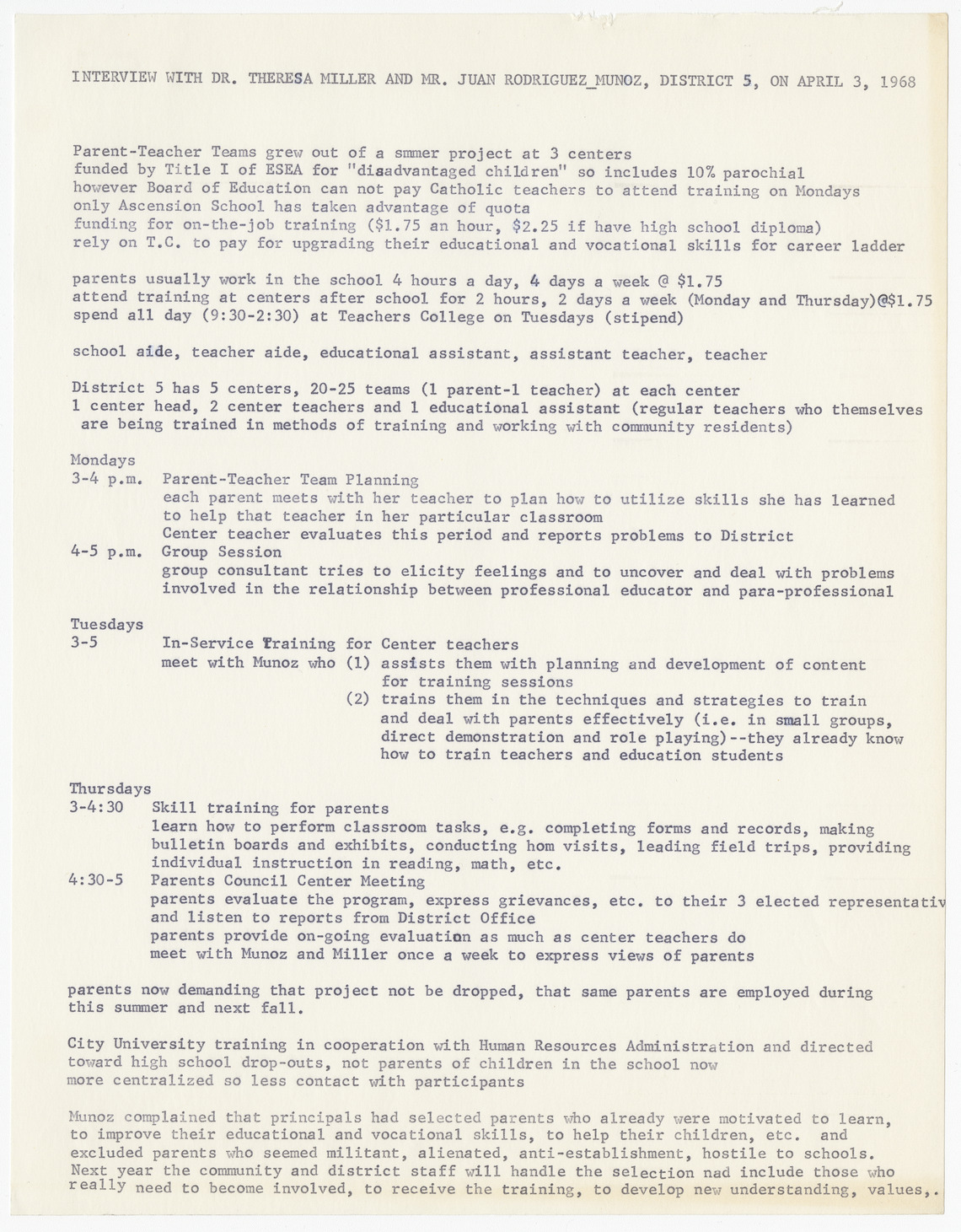

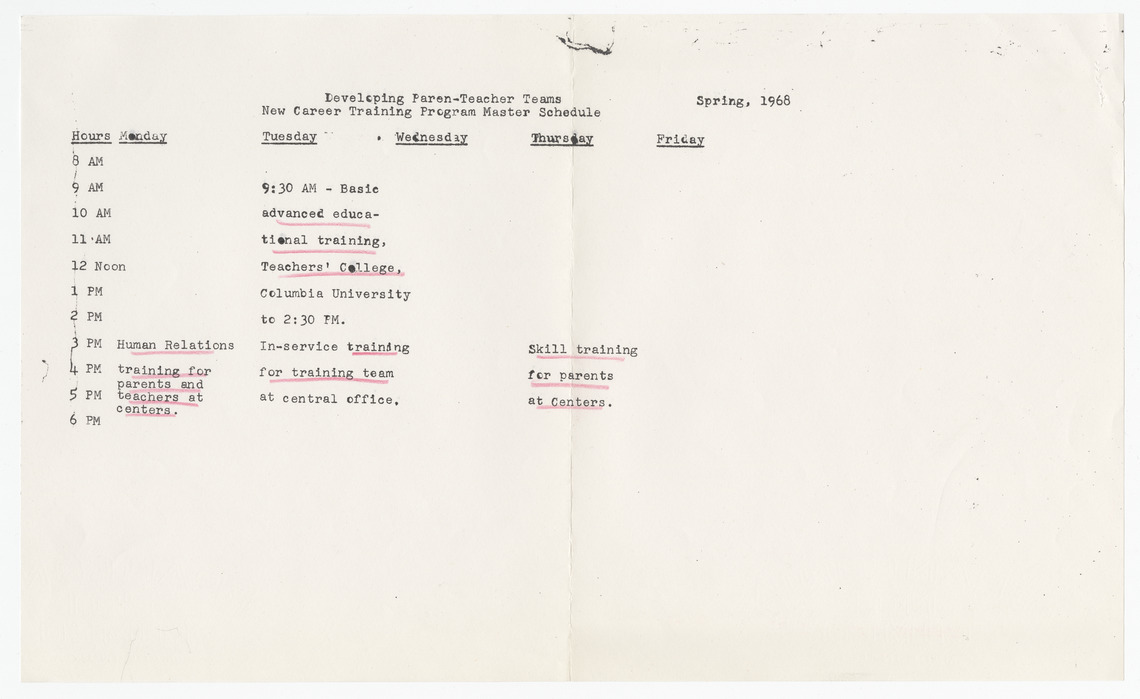

Professional Development: Improving Classroom Practice

The 27 schools in the program were divided into five Centers, administrative clusters that each designated a central school for District-led after-school trainings. The schedule, pictured below, was broken into three blocks.

- Mondays were reserved “Human Relations Training”, which consisted of one-on-one meetings between parents and teachers followed by group sessions meant to build cooperation between the two groups.

- On Tuesdays, teachers gathered for training while parent educators attended classes at TC.

- Thursdays were used for “Skill Training” followed by parent educator meetings with their elected Parent-Council representatives.

Creating Career Opportunities for Parents

The immediate economic impact of paraprofessional programs like Parent Teacher Teams are visible when we compare maps of paraprofessionals' residences in Harlem and the Upper West Side. Each blue dot on the map represents a job for a working mother, previously on or eligible for welfare, that paid roughly $2 an hour without requiring childcare. These jobs were coveted - across the city, hundreds of applications poured in to paraprofessional programs – but they were far from lucrative. Parent educators could not live on their wages alone, much less raise a family. In addition to jobs, Parent-Teacher Teams promised “an opportunity for parents to upgrade their academic backgrounds and career horizons." Teachers College ran this program on Tuesdays for parent educators, who received a small stipend for their attendence. Most worked toward high school diplomas, while those who had already graduated sought college credit.

Above: TC Week

Professor Hope Leichter (pictured) designed the academic program for parent educators. Working toward a diploma, she noted, was a "long haul" for many working mothers, but as one of her faculty told Morningside Heights, Inc. “School personnel and TC staff agree that the parents seem alert, enthusiastic and eager to learn both educational and vocational skills.”

Planned and Unplanned Consequences

For those parent educators who earned diplomas, the academic training program at TC provided by Parent-Teacher Teams was undoubtedly useful. However, the process of bringing parents "up the hill" to TC made an unintended impact on the program that mirrored some of the larger consequences of paraprofessional programs citywide. First, as evidenced by the quote above, poor and working-class Black and Latina mothers demonstrated their desire for educational and economic opportunity. In doing so, they offered a rebuke to the "culture of poverty" thesis, popularized in antipoverty circles through the work of anthropologist Oscar Lewis and made famous by the publication of Daniel Patrick Moynihan's 1965 Report "The Negro Family: A Case for National Action." "Matriarchal families" were singled out in this report as productive of pathology, harmful environments for children that were led by women without "middle class values." The tireless work of parent educators in classrooms - both in elementary schools and at TC - undermined these stereotypes. Second, bringing parents together to train in many ways encouraged parents to define and advocate for their own visions of paraprofessionalism in education. As noted on the previous page, parent educators sought certifications from their District training as well as their formal academic time at TC. This effort to shift the landscape of credentialing was bolstered by parent demands for representation in the planning process. This campaign by the Parent Council demonstrates that the mothers who became parent educators through Parent-Teacher Teams were not merely empty vessels or grateful recipients of the program's benefits, but worked to define and shape their jobs and training to make them practical and effective. Finally, bringing parent educators, teachers, administrators, and professors together at TC helped further the process of challenging the spatial and social inequities of Harlem. As Hope Leichter recalled, years later, "I think the most enthusiastic moments of the project were the actual encounters here and the course and the discussions and this incredible sense that these were people with amazing knowledge and understanding." Parent educators also gained access to TC's facilities, which included an extensive library with a large, comfortable children's section and a swimming pool and other recreational areas. Mothers brought children and other family members to the College to play and learn, a process that Hope Leichter remembers below as "welcoming and democratic."Hope Leichter: You do things and you don't always know all the implications as you're doing them. You don't quite know what's going to unfold. But I think it was welcoming and democratic beyond what we in some ways would have consciously been able to plan.

Paraprofessionals taking a high-school equivalency exam, Manhattan, 1970. (Photo Credit: United Federation of Teachers Hans Weissenstein Negatives Collection, Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU, via LAWCHA Labor Online).

[CHECK - replace with image as item]Training after Parent-Teacher Teams

The faculty and staff who worked with Parent-Teacher teams were unable to secure a true "career ladder" program for parent educators. However, models like Parent-Teacher Teams inspired New York City's paraprofessional educators to make paid educational opportunities part of their landmark contract with the city in 1970. Beginning in 1971, paras across New York City attended the City University of New York (CUNY) as part of an expanded "Paraprofessional-Teacher Education Program." In the clip below, Shelvy Young-Abrams describes the centrality of this program to the paraprofessional experience in those years.Shelvy Young-Abrams:One of the things that struck everybody was the fact that we were given the opportunity to go to school. We were given an opportunity to make our life better. We were given an opportunity to help. Matter of fact, because we had paras who not only worked during the day, but they also worked in a lot of community agencies after work, so they had enough time, had enough knowledge and enough respect to do that. We gave each other hope that there was a way out of this whole bondage that we were in, and the only way to do that was by following the footsteps that we were going in, which was following the union movement. That's for all the minorities, the Hispanics, the blacks, and all that, especially women. I think the challenge was to make sure we continue that fight and not turn around, and you'd be surprised how many of us became teachers. Thousands of paras became teachers, I mean thousands became classroom teachers.

The Limits of the Grant Model: The End of Parent-Teacher Teams

Hope Leichter, TC:"It came to an end. We didn't get the funding. I think it was partly that we couldn't deliver on the career ladder. It's partly that one of the funding models at that time, and subsequently, was seed money. That was very prevalent. And I can't tell you the details of how that worked out ... whether we were supposed to, for renewal, we had to bring in a certain amount of money or not. I can't tell you that. It may be in the files. And I didn't do all the financial negotiations. But the model was seed money. And again, I think that's often [the case] with start-up community projects, not just then, but subsequently ... there's some notion of "a foundation or a government gives a grant, if it's really good, then somebody else is going to pick up the tab to continue it." And it doesn't happen that way, always. So it had very heady moments ... and very painful aspects to it. And for me, it was very hard because I failed. I managed to run a very exciting, good program, bring people here and have a lot of people just cheering and thrilled and happy ... But I didn't get anywhere in negotiating a career ladder or some sort of admissions preference." In the clip above, Hope Leichter describes some of the factors that led to the end of the Parent-Teacher Teams program. While it proved both popular and effective, the program lasted only two and a half years, and was shuttered in the spring of 1970. Ultimately, a trio of factors rooted in the larger challenges facing New York City's public schools undid this program:Decentralization of the School System: In 1970, the State of New York split the New York City School District into 31 sub-districts, a partial concession to demands for decentralization and community participation that had emanated from Harlem for decades. While the intention of this decentralization was to provide increased opportunity for programs like Parent-Teacher Teams to evolve, existing programs were often shuttered as District lines were redrawn.

Limits of the Career Ladder at Columbia: As Leichter notes, Columbia University's School of General Studies (TC did not offer undergraduate degrees) did not ultimately approve a college program for parent educators, which became a point of frustration for participants as well as the District. While paraprofessional educators were often promised the opportunity to become teachers in early programs, these opportunities did not materialize until paras in New York City unionized and bargained a measure for training into their contract in 1970.

The Grant Funding Model: Perhaps the biggest challenge, as Leichter notes, was the grant funding model. Both the Ford Foundation and, to a lesser degree, the ESEA, initially worked on a grant-and-demonstration-model basis. While such grants allowed for tremendous innovation, they also left projects vulnerable when priorities and politics shifted. After conflict arose around Ford-Foundation-funded community control districts in New York City in 1968, Ford began moving away from these sorts of direct interventions in community schooling, leaving programs like PTT with few options.

Community-Based Paraprofessional Educators in Harlem Beyond Parent-Teacher Teams

Despite the end of Parent-Teacher Teams, paraprofessional programs in public education continued to flourish in New York City. As the clipped articles to the left describe, the Central Board of Education began working with the City University of New York (CUNY) in 1968 to create a similar program to Columbia's. Cyril DeGrasse Tyson, the first director of HARYOU, took part in the process, saying the new programs were "encouraging minority people to move up the career ladder.” Paraprofessional educators themselves continued to organize, joining the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) in 1969 and winning their first contract in 1970. The contract included provisions that made it possible for tens of thousands of mothers to attend CUNY's "Paraprofessional Teacher Education Program" in the 1970s. Over 2,000 became teachers by the early 1980s, and thousands more earned associates and bachelors degrees along the way.Epilogue: Parent-Teacher Teams Today

Today, tens of thousands of paraprofessional educators work in New York City public schools, and over 1.2 mlllion people - still primarily women, 80% of them mothers - do this work nationwide. The program structure of paraprofessionalism has changed dramatically; today, over half of paras work in special education. While specific programs that encourage community engagement and pedagogical innovation still exist - one excellent example can be found in Soo Hong's book A Cord of Three Strands, which describes the evolution of parent-engagement efforts including the "Grow Your Own Teacher" Program - many paras today find their labor unacknowledged or marginalized in schools. However, the legacy of the paraprofessional movement lives on in the everyday labor of paras today, and opportunities to challenge the marginalization of these workers have re-emerged in recent years. Teacher unions, themselves under attack, are reaching out to paras to help them reconnect with communities. In suburban areas, parents have led the fight to preserve para jobs that have been threatened with outsourcing. Educators and scholars are developing new kinds of "reality pedagogy" for students defined as "neo-indigenous" whose lifeways and cultures are routinely dismissed or denigrated in schools, while a decline in recruitment and retention of Black and Latinx educators has led to renewed declarations that "Black Teachers Matter." Finally, the most recent reauthorization of the ESEA, the Every Student Succeeds Act, has set aside both funding and assessment for "community engagement" in schooling. In all of these contexts, community-based paraprofessional educators will have a role to play in the future.Credits

This exhibit was created by Nick Juravich. It began as an assignment in Professor Ansley T. Erickson's "Harlem Digital Research Collaborative" course in Spring 2014, and has evolved through a process of open review on the Harlem Education History Project website. Many thanks are due to all of the participants in that course, the reviewers, and the entire HEHP team for their support and recommendations. Special thanks are due to all of the educators who shared their experiences with us as part of this project. © Nick Juravich, 2017 This exhibit is a companion to the essay, <a href="https://harlemeducationhistory.library.columbia.edu/book/chapters/10“>"Harlem Sophistication: Paraprofessional Educators in Harlem and East Harlem, 1963-1983,"</a> in Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community. As I have worked on both of these projects, it has become apparent that chapters and exhibits have different logics. In the chapter, I am trying to make an argument, using sources that have been distilled to their pithiest, quickest form. When I started writing the exhibit, I was thinking the same way and foregrounding my writing, but as the exhibit evolved and passed through a process of open review, I have realized that the best parts of the exhibit cannot and should not be my writing, no matter how polished or pithy. The best parts of the exhibit are the photos, oral histories, documents, and the maps: the parts where a viewer sees, hears, and interacts with the sources. To that end, I have included as many of these sources as possible, and the exhibit makes use of oral histories and photos of paraprofessional educators and their allies from beyond Parent-Teacher Teams. While no programs or individual experiences were exactly the same, these photos and remembrances have been chosen to provide paraprofessional perspectives that are broadly representative of the experience of paras in these years. For additional information on these individuals, please contact the exhibit creator.Further Resources

Primary Sources

Archival Collections:

Morningside Area Alliance Records, Columbia University Archives (New York, NY)

United Federation of Teachers Records, WAG.022, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University (New York, NY)

United Federation of Teachers Hans Weissenstein Negatives Collection, PHOTOS.019.001, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University (New York, NY)

Periodical Collections (accessed via Proquest Historical Newspapers):

The New York Amsterdam News

The New York Times

Oral Histories (Three of these oral histories were conducted through the Educating Harlem Project and are available in full through our archive, as linked below. All transcripts are available from the author):

Lee Farber

Marian Thom

Shelvy Young-Abrams

Secondary Sources:

Scholarship and Reports on Paraprofessional Educators and Para Programs in the 1960s and 1970s: Many of these reports can be accessed via ERIC or WorldCat.

Brickell, Henry M. et al. An In-Depth Study of Paraprofessionals in District Decentralized ESEA Title I and New York State Urban Education Projects in the New York City Schools. New York: Institute for Educational Development, 1971.

Bowma, Garda and Gordon Klopf. New Careers and Roles in the American School. New York: Bank Street College, 1968.

Kaplan, George R. From Aide to Teacher: The Story of the Career Opportunities Program. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1977.

Mark, Jorie Lester. Paraprofessionals in Education: A Study of the Training and Utilization of Paraprofessionals in U.S. Public School Systems Enrolling 5,000 Or More Pupils. New York, Bank Street College, 1976.

Riessman, Frank and Arthur Pearl. New Careers for the Poor: The Non-Professional in Human Services. New York: The Free Press, 1965.

Introductory Materials: The following is a partial list of links to articles, websites, online resources, and digital exhibits that address some of the main themes of this exhibit in the past and present. If you would like to share a resource for this list, please contact the exhibit creator.

"Empowerment: A Voice for Paras and School Staff" American Federation of Teachers 100th Anniversary Video Segment, 2016.

"Demand for School Integration Leads to Massive Boycott - In NYC" WNYC - SchoolBook

"De facto segregation in the North: Skipwith Vs. NYC Board of Education" Jewish Women's Archive

"Paraprofessional Educators and Labor-Community Coalitions, Past and Present" Blog Post and Lesson Plan for the Labor and Working-Class History Association's Teacher/Public Sector Initiative (written by exhibit creator Nick Juravich).

Peter Aigner and Nick Juravich, eds. "New History of Education in New York City: A Roundtable" Gotham Center Blog, July-August 2016 (entries listed below, with interpretive replies from Heather Lewis and Brian Purnell)

- Michael Glass, "A Series of Blunders and Broken Promises: I.S. 201 as a Turning Point"

- Barry Goldenberg, "The Story of Harlem Prep: Cultivating a Community School in New York City"

- Nick Juravich, "Making a Paraprofessional Movement in New York City"

- Lauren Lefty "Decentralization, Decolonization, and the Not-So-Local Dimensions of Local Control"

- Dominique Jean-Louis "Education Activism in Parochial Schools in Post-Civil-Rights-Era Brooklyn"

- Jean Park "From Culturally-Driven to Market-Driven: Academic Success and Korean Cram Schools in the New York Metropolitan Area"

Works of History: The following is a partial bibliography for education and activism in New York City in the 1960s. Scholars continue to debate and re-interpret this era actively, including major events such as the 1964 Schools Boycott, the 1967-88 experiment in "community control" and the ensuing teachers' strikes, and the 1970 decentralization of New York City's school system.

Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2005)

Jane Berger, “'A Lot Closer To What It Ought To Be:' Black Women and Public Sector Employment in Baltimore, 1950-1970,” in Robert Zieger, ed., Life and Labor in the New New South (Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 2012)

Tamar W. Carroll, Mobilizing New York: AIDS, Antipoverty, and Feminist Activism (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

Christina Collins, "Ethnically Qualified’’: Race, Merit, and the Selection of Urban Teachers, 1920 - 1980 (New York: Teachers College Press, 2011)

Joshua Freeman, Working Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II (New York: The New Press, 2001)

Richard D. Kahlenberg, Tough Liberal: Albert Shanker and the Battles over Schools, Unions, Race, and Democracy, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007)

Sonia Song-Ha Lee, Building a Latino Civil Rights Movement : Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and the Pursuit of Racial Justice in New York City (Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 2014)

Heather Lewis, New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and Its Legacy, (New York: Teachers College Press, 2013)

Nancy A. Naples, Grassroots Warriors: Activist Mothering, Community Work, and the War on Poverty, (New York: Routledge, 1998)

Daniel Perlstein, Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang, 2004)

Jonna Perrillo, Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2012)

Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002)

Wendell Pritchett Brownsville, Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews, and the Changing Face of the Ghetto (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2002)

Diane Ravitch, The Great Schools Wars: New York City 1805-1973 (New York, Basic Books, 1973).

Clarence Taylor, ed. Civil Rights in New York City: From World War II to the Giuliani Era (New York, Columbia Univerisy Press, 2011)

Clarence Taylor, Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union (New York: Columbia University Press: 2013).

Clarence Taylor, Knocking at Our Own Door: Milton A. Galamison and the Struggle to Integrate New York City Schools (New York: Columbia University Press: 1997)